Understanding Brick Siding Systems

Most brick houses today are not what they appear to be. They are, in fact, wood houses that have decorative (yes, decorative) brick siding that essentially performs the same functions as wood plank or vinyl siding. The bricks may look stout and structural, but they're not supporting anything other than their own weight. Real brick, or "solid masonry," houses, started going out of style about a century ago, and almost all brick homes now are simply sided with brick. To confuse matters further, there are different types of brick siding, but the classic style is made with real clay brick laid with mortar.

Traditional Brick Siding vs. Thin Brick

Traditional Brick Siding vs. Thin Brick

Brick siding is also called veneer brick (or brick veneer), which clearly distinguishes it from solid brick construction. However, this doesn't help define what kind of brick siding it is. A traditional brick veneer is built by a mason and is laid up with full clay bricks that are stacked, with layers of mortar in between. A newer species of brick veneer, often called "thin brick," is made of thin brick faces (down to about 1/2-inch thick) that are installed much more like ceramic tile than traditional building brick. In many cases, the brick faces are made from concrete rather than clay. The thin bricks are stuck to the house wall with adhesive, then the gaps between bricks are filled with grout to simulate structural mortar joints.

Supporting Brick Siding

Supporting Brick Siding

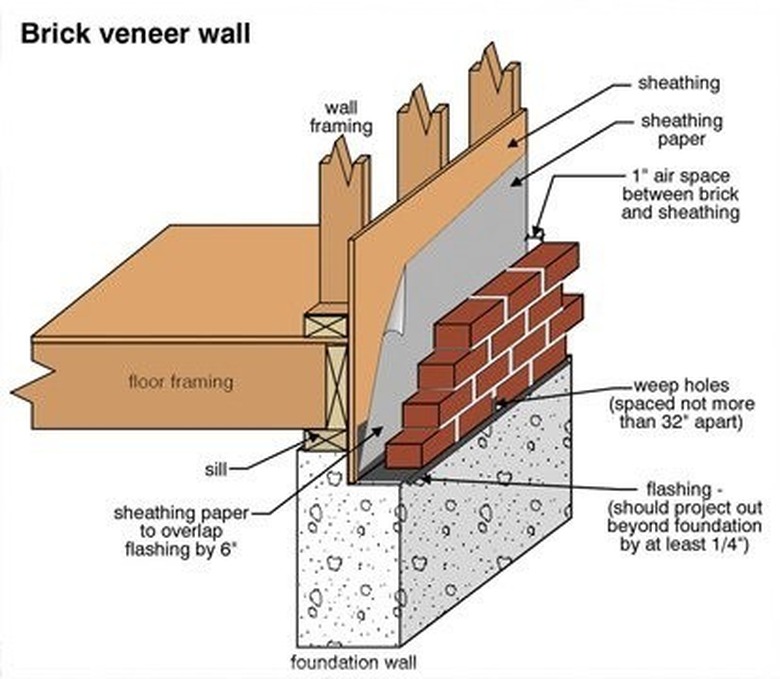

Traditional brick siding (not thin brick) is quite heavy and therefore needs a strong, solid foundation. On many brick-sided homes, the concrete foundation walls or footings have a little step cast into them for supporting the brick. Alternatively, the brick can be supported by heavy iron angle that is mounted to the foundation wall, creating a shelf for the brick.

The weight of the brick siding is supported by the step or shelf. That takes care of the vertical, or downward, load of the brick. The horizontal load of the brick siding is partly supported by the framed wall behind the siding. Brick siding is laid in a single stack (called single wythe), which, despite appearances, is not highly resistant to wind and earthquake forces. Therefore, it must be anchored to the framed wall with metal ties cemented into the mortar joints. The ties typically are placed every 24 inches vertically and 32 inches horizontally all the way up the wall.

There’s Air Behind Brick Siding

There's Air Behind Brick Siding

One of the more surprising aspects of a brick siding system is the fact that the brick and the wood wall behind it don't actually touch. In fact, they must be separated by at least 1 inch, according to building code. This creates an air space that helps the wall assembly shed moisture. Also, wood and brick expand and contract differently, and the separation allows the two structures to move independently; without the gap, you might end up with cracks in the brick wall. The metal ties that anchor the brick siding to the framed wall are flexible enough to allow for this movement.

Brick Siding Materials

Brick Siding Materials

Traditional brick siding uses standard clay bricks, but instead of full-size construction brick, called engineer brick, siding usually consists of queen brick, which is about 3/4 inch narrower than engineer brick. This smaller dimension makes queen brick 30 percent lighter than standard building brick, and it uses almost 25 percent less mortar. The length and height of queen and engineering brick are the same, so you can't tell them apart by looking at the face of the wall.

Brick veneer also can be made with other shapes and sizes of brick, such as the flat, long bricks commonly found on mid-century brick homes. The brick can also have any kind of facing or texture, just like building brick. Mortar used for constructing brick veneer walls typically is Type N, which is a medium-strength mortar suitable for above-grade, non-load-bearing walls.

Building a Brick Siding Wall

Building a Brick Siding Wall

Because brick siding isn't part of a home's structure, it can be installed anytime after the framing is complete, and it doesn't have to hold up the rest of the house construction. Like other types of siding, brick veneer typically is installed after the house is "dried in" and has the windows, doors and roofing in place. The wall to receive siding typically is covered with plywood or another type of structural sheathing followed by building paper (tar paper) or other water-resistive barrier (WRB) material.

Once the framed wall is ready, the brick veneer goes up much like a freestanding brick wall, starting with a mortar bed under the first course of bricks, then another layer of mortar on top, followed by the second course, and so on. In addition to the anchor ties, building code requires flashing below the first above-ground course of brick. The flashing attaches to the framed wall and forms an "L" shape, with the bottom leg extending over the brick. It's there to channel water out of the space between the wall structures.

Another requirement is adding _weep holes_—gaps between neighboring bricks that let water and moisture escape. These are placed in the first course above the flashing and are spaced no more than 33 inches apart.

Where brick siding butts up to window sills, a course of angled "rowlock" brick creates a sloping shelf to shed water and provide a finished look. Where brick siding extends only partway up the wall, the top of the brick may be finished with a rowlock course, a masonry cap or wood trim to transition to a different siding material above.

Maintaining Brick Siding

Maintaining Brick Siding

Capable of lasting hundreds of years with little maintenance, traditional mortared brick is far-and-away the most durable siding material available. It's perfectly normal for brick siding to show very little sign of wear or damage after several decades. And this is without sealers, paint or other protective coating of any kind. In fact, the quickest way to turn a brick wall into a regular maintenance issue is to paint it.

The most common maintenance task for brick veneer is repairing or replacing cracked or crumbled mortar. This usually occurs in isolated areas and is typically caused by years of weather exposure, particularly rain and freezing water (in cold climates). Once cracks or chips appear in the mortar, they make room for more water, snow and ice to get in, compounding the damage. The solution for damaged mortar is to scrape out the cracked, loose material and replace it with fresh mortar. This technique is called pointing or tuckpointing.

In small areas, tuckpointing can be done by homeowners (just make sure to use the right type of mortar), but widespread repair is best left to professionals. More significant wall damage, such as long and/or wide cracks that may indicate foundation problems, also should be left to pros.