Take A Look Inside Ceramicist Michele Quan's Brooklyn Studio And Home

At any given time, Michele Quan's Brooklyn studio is working on hundreds and hundreds of online, wholesale, and custom orders for the hand-built and wheel-thrown ceramic art and objects sold under the label, MQuan. A few other ceramicists work out of the Gowanus warehouse, sharing a single kiln; but more than half the square footage is being used — maximized, ideally — by Quan, her team of studio assistants, and the thousands of hunks of clay they are babysitting.

"Clay needs to dry, it needs to set up, it needs to have a place it can call home for while," Quan says, standing in front of a sizable table stacked with several rows of large inch-thick clay discs loosely covered in newspaper and cloth.

They've been slowly drying for over a week, and once they reach a stage described as "leather hard" — stiff, but still moist and malleable — they'll be cut and assembled into hollow, half-moon-shaped objects she calls "Half the Sky." They'll eventually be hand-painted with glaze in multiple variations that reflect her distinctly raw but refined take on several recurring themes.

"I kind of went crazy with the sun, moon, and stars," Quan says, referring to three of the universal symbols that appear throughout her work. "Black and white, the morning and the night ... that kind of encompasses everything. They're really straightforward, but they mean something to everybody. Everyone has that experience of looking up at the stars and being like, 'Holy fuck.' It's awe-inspiring, but it's not complicated. Everyone gets it, everyone relates to it. It's common, but it's also strangely really deep."

When Quan moved into the studio four years ago, one major perk was the large skylight in the ceiling that floods the much of the warehouse in natural light.

"I kind of went crazy with the sun, moon, and stars ... It's awe-inspiring, but it's not complicated. Everyone gets it, everyone relates to it. It's common, but it's also strangely really deep."—Michele Quan

"My old studio was in Williamsburg in an old brick building owned by Arnie Zimmerman [a well-known contemporary ceramicist] — I had no air conditioning for three years. He had this really old forklift that smelled like gas and it was just, like, stinky, but I loved going there. I called it Macho Studios. So when I moved here, I called it the Princess Studio, because there was a drain on the floor, heat, air-conditioning ... the skylight!"

A few months ago, Quan began subletting additional space at the very front of the building, where hours of direct sunshine beam through windows on nice days. She points out a few potted plants sitting on bookshelves and says they almost died. "The plants are happy now!"

The sublet is temporary, Quan says, a "present" she gifted herself after she kept delegating all of the available studio space to the growing team of assistants who are essential to running a smooth, successful, sustainable business producing handmade, slow-crafted objects at a relatively large scale. The shelves along the wall holding Quan's plants are among the few spots in the studio that aren't completely commandeered by dozens and dozens of in-progress ceramic forms that Quan has become known for — a mixture of clearly functional pieces, like planters, large cylinders and bowls, trinket dishes and incense burners, and more ceremonial, decorative, and sculptural objects, like chain links, garlands, wall-hangings, and bells.

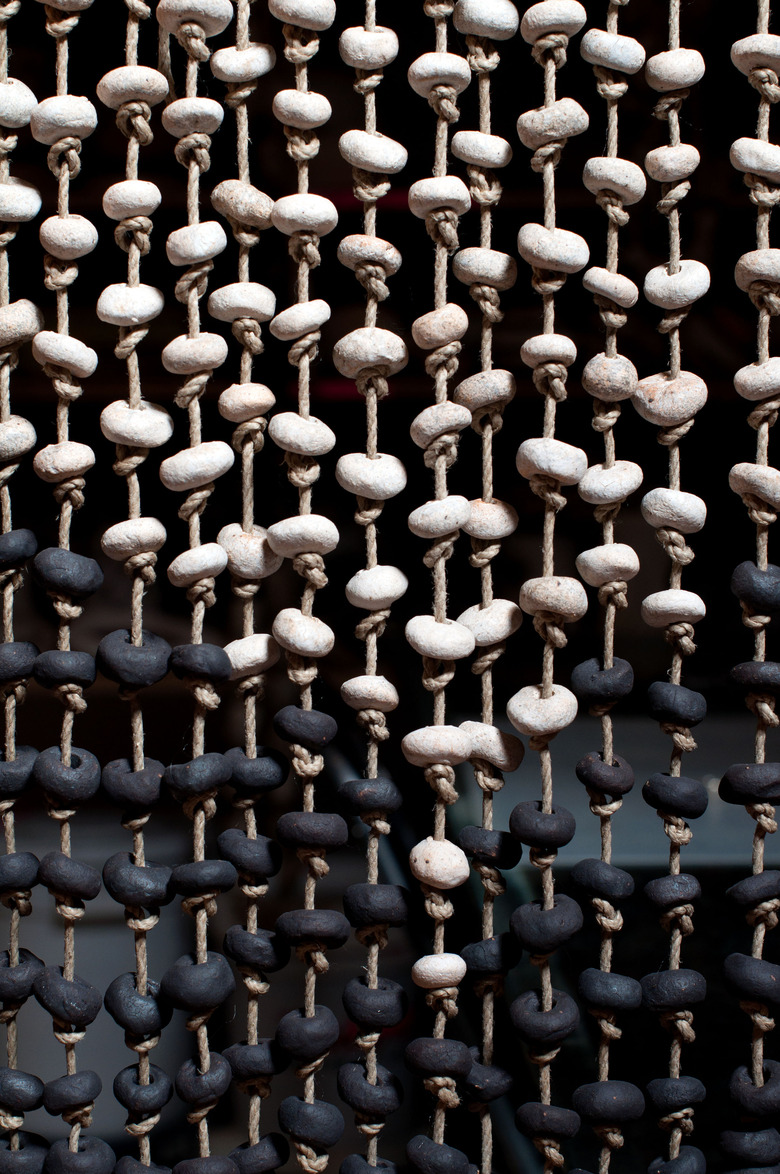

The production volume, the slow, multi-step process, multiple kiln firings, all that babysitting, not to mention packaging and shipping orders, requires Quan to run a tightly organized ship. Ceramics requires a lot of attention and focus, so there's not a ton of chatter while Quan's assistants (all of them women) work intently in their particular area of expertise, throwing cylinders that will be turned in bells, slipping and scoring slabs of clay together into multi-sided objects, and hand-forming individual beads that will eventually be strung on hemp rope and sold as garlands.

Twenty years ago, Quan's creative pursuits, and her first successful business endeavor, were all about adornment. Quan is the "Me" in Me & Ro, a line of fine jewelry, beloved by fashion editors, stylists, and celebrities for its delicate simplicity and artful use of eastern iconography. (Many of Quan's ceramics feature delicately painted Sanskrit, which has been a big source of inspiration since she read the Bhagavad Gita.)

Born in Vancouver, Quan moved to New York City in 1984 to study graphic design at Parsons [School of Design], but dropped out after a year and a half.

"I worked at a bar called Area and a restaurant called Indochine," Quan says, naming two of the city's trendiest venues at the time. "And it was just the '80s. School was also really expensive — Parsons was $11,000 a year. That was a lot [back] then and I couldn't afford it."

Working at Indochine was how Quan met and became friends with Robin Renzi, otherwise known as "Ro."

"She knew how to design jewelry, and I loved buying jewelry," Quan laughs. "It was her idea [to start a business], I think. So, I spent a summer in San Francisco and took a class from this guy in Oakland, and then Robin showed me how to do a few things — but I kind of taught myself how to make jewelry. I feel like if you have the right tools, you can kind of teach yourself a lot of things ... I set up a little table in my apartment and I had a little toy butane torch ... I was really just sitting around wanting to make things. When you have that desire to make something, and you have the idea in your head, you figure it out. And that's what we did."

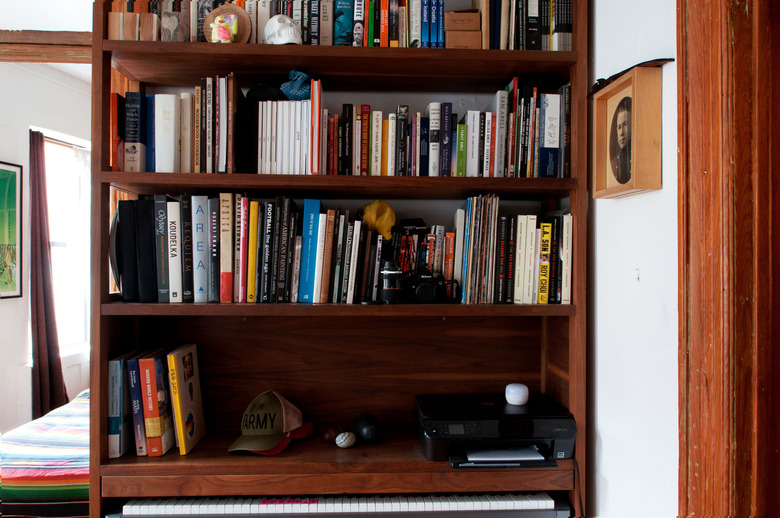

Me & Ro launched in 1991, the same year that Quan moved into the third floor walk-up apartment in SoHo that she still calls home, only now her husband, a photographer, teenage daughter, Elsie, and eight-year-old dog Sparrow share the 500 square foot space (it's rent-stabilized!). Luckily, the apartment has the more coveted elements of an old New York City tenement building, like a deep clawfoot bathtub and farmhouse sink; amber-hued hardwood floors and molding; and blue and white decorative tiles in the bathroom. It's the kind of New York City apartment that realtors would describe as "charming," and for once, actually mean it.

Quan had dabbled in ceramics at several points in her life — in the early '90s, she took a wheel-throwing class at the YMCA on Manhattan's Upper East Side and really enjoyed it, but soon got caught up with the day-to-day of running her own business. Then, for about eight months in 2002-2003, Quan spent her Saturdays making pinch pots with ceramicist Adrienne Yurick at Third Ave Clay in Brooklyn.

After 12 years, Quan left Me & Ro in late-2003, when Elsie was born (Renzi now runs the business solo). In 2005, full-time stay-at-home motherhood was making Quan a little bit antsy, and she found herself gravitating towards ceramics once again.

"I was like, 'I need to do something,'" Quan says. "I knew I needed to start something else eventually or get a job or figure something out, so I was kind of stressing out about that a little bit. Elsie was 14 months, she was walking, and it was a lot of work, and I was just, like, oh my God I need to get out of the house. So I said, 'oh fuck it, I'll just take a ceramics class,' because I knew I liked ceramics ... and then I just kind of fell in love with it. Like the rest of the world is doing right now."

For years, Quan took classes and developed her skills at Greenwich House, a studio in Manhattan. She was primarily obsessed with making, surprise, surprise, beads and garlands, which she imagined being wrapped around trees as offerings. Quan also began to really refine her ceramics process and point of view, learning practical tips and tricks, as well as deeper lessons, from her fellow potters. Making ceramics, in addition to being slow, can be a fickle process and even the most perfect pot made by skilled hands can be easily ruined.

"I would spend so much time perfecting a bowl and then I would be like, 'Oh, fuck, I haven't even thought about glazing, this could just ruin the whole thing!'" Quan says. "I would get stressed about what to do next ... I was too attached to it. Then somebody suggested that I cut the bowl in half, so it was nothing. After that, I spent months making pinch bowls, cutting them in half, and using the pieces to do glaze tests."

Her distinctive, recognizable color palette and loyalty to materials reflects Quan's Zen-like pragmatism. She's used the same tan, groggy clay body for years, dipping her pieces in a layer of thin white slip before its first firing in the kiln, which softens its natural toastiness just a touch. Her version of a rainbow contains matte glazes in red, orange, indigo and, her favorite, marigold, but no green or purple, because they just aren't her thing. In addition to her rainbow glazes, Quan favors matte black underglaze and a color called Temple White, that has just a subtle sheen.

"Someone once gave me really good advice —'Pick your three favorite glazes and then to exhaust them,'" Quan says. "Because with the three glazes, you already have so many variables that you can play with. I've tried to pass that on to other people who are doing ceramics — don't jump all over the place. Pick the few things that you love or that you feel for and just exhaust them and see where that leads. Otherwise, it's overwhelming."

Quan's desire for balance and simplicity amidst chaos is reflected in the contrasts between her studio and her home. Her Gowanus studio is stacked, wall-to-wall, with Quan's works-in-progress and the many necessary tools for making and babysitting them. The finished pieces, all glazed and fired, provide plenty of colorful adornment.

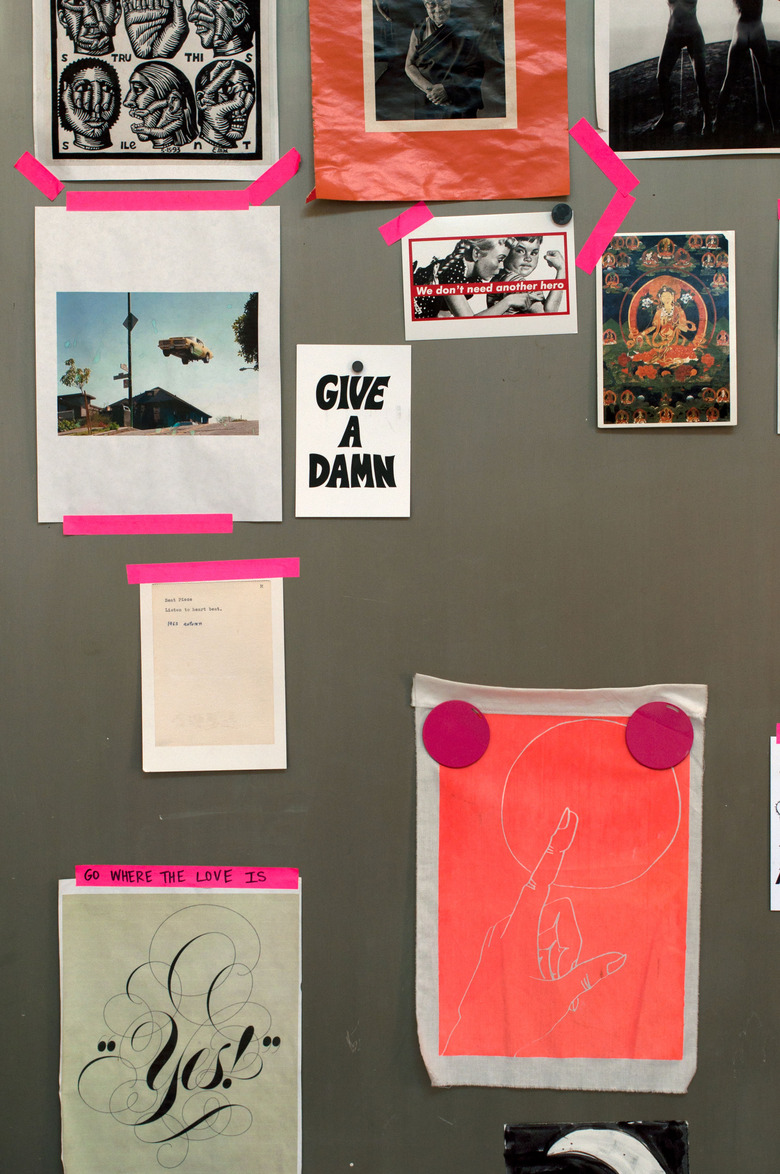

Her apartment, on the other hand, contains just two pieces of her own work — a small hollow, painted ceramic rock, which sits in the center of a small coffee table in the living room; and a large cylinder planter with a painted eye that holds cooking utensils in her open kitchen. There's an array of other artwork on display, like the thoughtfully curated gallery wall behind the couch featuring paintings and portraits by Elsie and Quan's step-daughter, Bobbie Jean; photographs by Quan's longtime partner, Bobby Fisher; a rainbow painting by the artist Ann Tracey; a fried egg art piece by Sean Bluechel; photos of Neil Young (by Henry Ditz) and Joe Strummer (by Bob Gruen), and a painting of Hank Williams by Jon Langford from the band the Mekons. In the corner stands a Isamo Noguchi lamp that's missing its shade but Quan swears she's going to replace someday.

Eventually, Quan wants to move her family upstate to the Catskills area, buying property and, finally, her own kiln. Relocating her business will be no small undertaking, but any stress is more than balanced out by the prospect of having so much space.

"I make things for my big country house. I don't have it yet, but in my mind, I'm making things for my garden, all the trees..." Quan walks over to a bench in her studio, where a large, round dish sits. "I started making these ... for beside the front door. I call it 'the reliquary' because it's a platform for your collection of found objects. You know, when you go on a walk and pick up shells and sticks, where do you put them? And in my mind, I put it all in there.

Words by: Amelia Amelia McDonell-Parry

Images: Chloe Berk