This 3,500-Square-Foot Studio Is A Museum Of Artifacts, Vintage Treasures, And Makeshift Shrines

Inside a nondescript warehouse located in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles — wedged between abandoned factories, auto body shops, and medical marijuana dispensaries — artist and creative director Justin Bauer stands behind a live edge wood slab bar, burning a lemon rind over a thrift store whiskey glass. Behind him sit rows of mismatched glassware, found objects, and two painted portraits sloped impossibly outward as if levitating off the wall. It's only one in the afternoon, but the absence of daylight combined with the Blade Runner soundtrack "Tales of the Future" playing forebodingly in the background suggest otherwise. His sprawling 3,500-square-foot studio is a universe unto itself, meticulously decorated as a museum of artifacts, vintage treasures, and makeshift shrines. It looks as though the Magic School Bus has shrunk and descended upon the artist and creative director's consciousness: welcome to the Warehouse Acropolis where we are invited to explore.

Bauer has spent the last six years building his Boyle Heights studio, using sensory experiences and mood as a means to dictate his decor over practicality and function. "My aim was to section an area to give me mental structure," he says, "this zone here, that zone there, but also keep it open and expansive and include a feeling of possibility."

To the untrained eye, nothing makes sense: there is a bathtub in the kitchen, a warped car part taken from a friend's car crash stuck to a wall, a faux fireplace flickering inside of a hollowed out TV, and a dried tree branch leaning precariously in the middle of the room. Bauer built out much of it by hand. "I'll always find a way to make something myself. Like all of the light fixtures — I found one of those perforated dryer drums in the alley, cleaned it up and repurposed it into a big can overhead light. I love perforated things," he says.

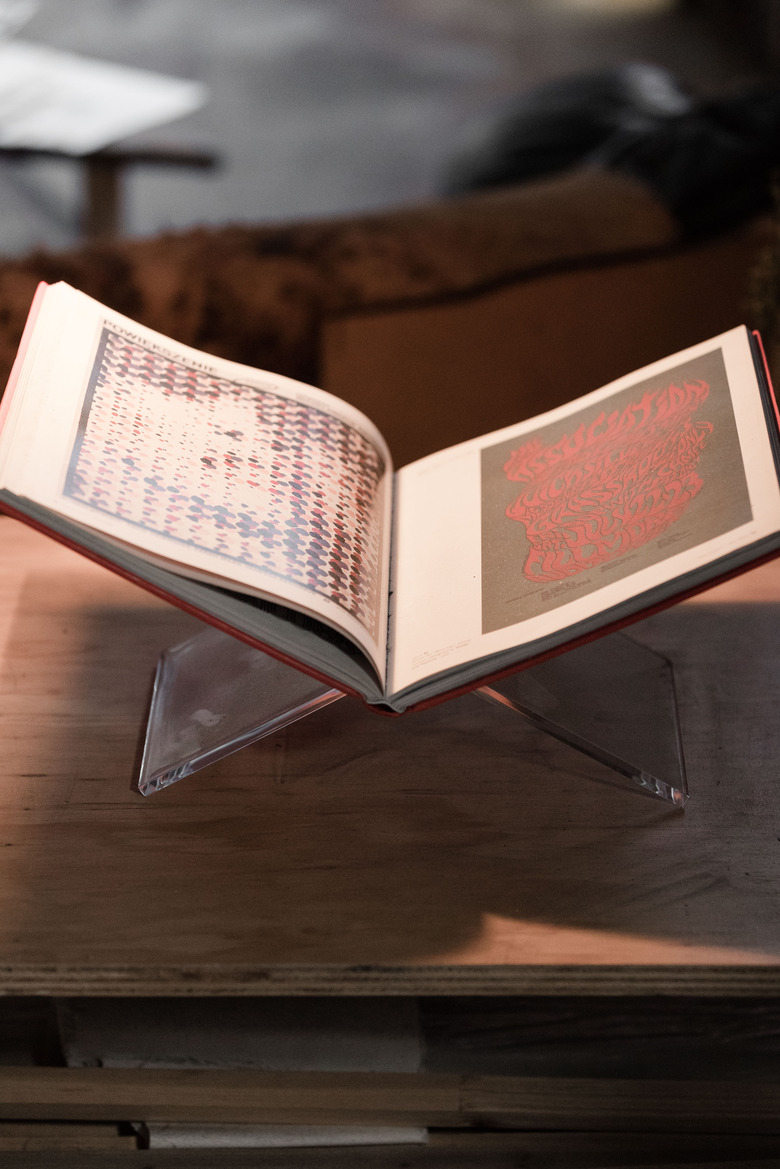

The rest he scoured from online and secret secondhand shops. The result is an eclectic mix of eras from 1960s Palm Springs pool chairs to a solid wood medieval dining area, then to piles of 1970s Moroccan rugs arranged in a manner that feels more sci-fi than bohemian. "Anyone who knows would see the Blade Runner connection in some ways — I've always liked hard industrial angles mixed with some earthy stuff," Bauer says.

It's not just space he considers, but that synergy between spaces and objects. Bauer fine-tunes aesthetic elements like an alchemist to achieve desired states: How might the resonance of the ambient music complement the lighting, would it evoke a state of calm and productivity? What about the faux vines coiled around industrial pipes like dollar store tinsel, would it create a celebratory backdrop for a social gathering? That's because the Warehouse Acropolis is not just the artist's sanctuary, but also an occasional communal event space for artists of all kinds to perform and gather in Bauer's otherworldly spaceship. As a self-proclaimed recluse, he enjoys the occasional company that comes with hosting events, according to Bauer, "It's nice to be working in here for two weeks straight alone and then just have a bunch of people come to me and hang out." When asked if he ever gets nervous about so many people being in his space and rummaging through his belongings, he seems unbothered, joking "but really, whoever stole that gold-plated cobra incense burner from the bathroom, just know that one day the cobras will find you."

Dozens of both high-profile and emerging musicians, writers, and artists have performed at the Warehouse Acropolis, but Bauer's original intent was to seek out some isolation; a place where he could paint. "The main thing was, where am I going to paint? Working in a large space forces you to come to terms with limits, there are less limitations," he says. "Artists impose a lot of stupid psychological barriers onto themselves, which is part of the process, but you have to confront that pretty regularly when there's more air around you."

Bauer is not the Willy Wonka character one might expect after walking into his space; he co-runs a magazine about character called Wilderness, works with high-profile brands, and drinks La Croix. He is, by all accounts, normal. His abnormal setup was borne out of optimization and personal progress. "With creative practice and discipline," he says, "I think it's important to keep moving. If I can split my day doing some mundane design, then 20 minutes of writing, then do some absurd wild painting, I'm keeping this stimulation cycle. It's different work but it's connecting itself, being fluid. The same thing happens with the space: I'll feel stagnant and then realize I need to build something or rearrange and that actually reinvigorates me. Plus it's like, how can I improve this or legitimize this light fixture made out of cardboard that I got from iPad packaging."

Much of his time, when not tending to client work, is devoted to working on large-scale paintings while listening to obscure records and ambient recordings. "I listen to a lot of ambient stuff," he says, "it's not uncommon to come in here and hear what sounds like science fiction cars faintly flying outside. Nature sounds, too. I listen to Autechre, Aphex Twin, '90s Bowie (Heathen, Earthling) Nicolas Jaar; been listening to a lot of Carla Dal Forno, The Fall, The Cure, Skee Mask, Suicide and Iggy this week. I also like Paul Simon." Sonic textures amplified from every corner make the experience of simply standing in the center of the room seem surreal and cinematic; this is especially true if you find yourself accidentally standing beneath the glowing disco ball like you're in a John Hughes movie.

Maybe it's because he's spent so much time here, but the more eccentric, theatrical elements of the space seem almost commonplace to him. It's not that he doesn't recognize that living inside a constantly evolving art installation seems strange to most, he's just used to it at this point. His even-keeled temperament extends to the loud bangs and creeks of the space. When an Amazon package thudded against his front door, for instance, he didn't flinch as I did — he already knew what it was by the sound. He goes on to tell me about the man he once chased off the roof with an 1800s Winchester rifle: "He was drunk and trying to get in through the skylight. Ultimately he said he just wanted to explore," Bauer says, laughing.

When asked about living in the neighborhood of Boyle Heights, which has become symbolic of the tension of LA's aggressive gentrification efforts, Bauer recognizes his place in the cultural discourse with a deep reverence for his neighborhood and his desire to advocate for and not interfere with the already rich culture there.

"l really feel accepted," he says, "I don't really want anything to change, I'd prefer to hide and absorb the culture that already exists. These people are honest, kind, hard-working and deserve the highest respect. When I heard the rent was increasing near Mariachi Square and driving Mariachi's out, I got really sad. I personally think developers are the problem. If you're an artist, as much as your craft is central to you, it is also primarily about people. The conversations you have within culture, the relevance to humanity-at-large. Conversations with yourself are ultimately cyclical and therefore unevolving." He goes on to reiterate, "Boyle Heights is an amazing place full of character and I hope it stays that way. For me it's about listening and respecting, not changing the culture around me."

Beyond a place to work, the space is a living, breathing retrospective on Bauer's life, art, and friends. When I asked him what his favorite piece was, he first pointed to the painting of a lady, the one hovering — a gift from a friend. A bust of Puccini he bought for a dollar because it reminds him of when he lived in Italy, and a hamburger bank given to him by his friend Ethan. Everything here contains meaning and story.

Sentimentality is used as a guiding principle. The Warehouse Acropolis represents a small tear in convention, away from what one ought to make of a home. Instead of the typical thirty-something urban dwelling with its easily replicated midcentury modern sensibility, nonthreatening color schemes, and neatly framed screen print posters, it offers a radical alternative: do whatever you want. Make a space that serves you, your adult tree fort, your own imaginary utopia. Whatever that means is entirely up to you.