When To Open A Bottle: Aging Wine Without The Anxiety

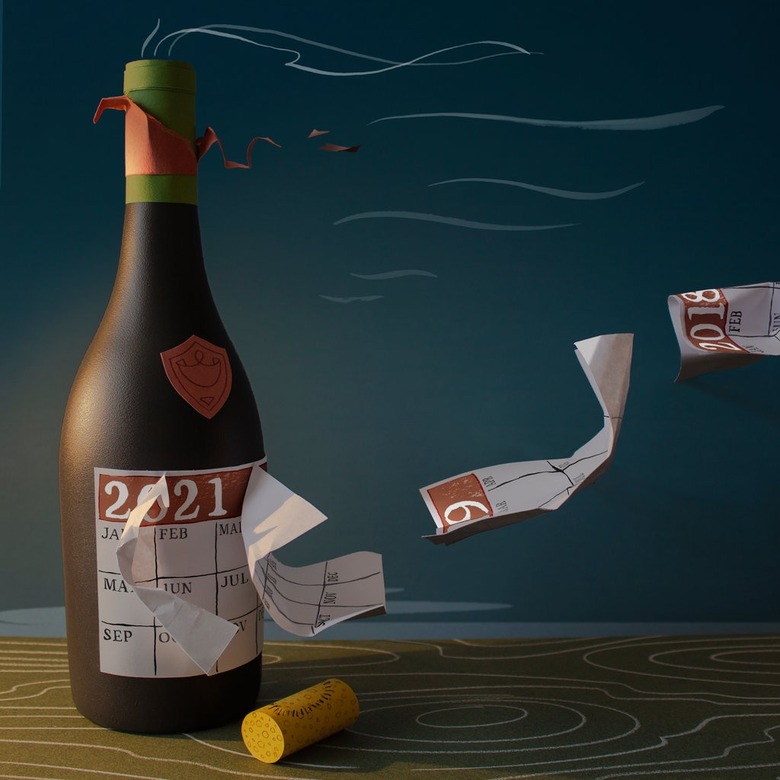

Aging wine is an act of hope and optimism, laced with fear and dread.

You dearly want to be rewarded by a bottle that matures from awkward, inarticulate youth to expressive beauty and, eventually, elegant complexity. The fear is of waiting not long enough or too long, of storing it wrong and, ultimately, of missing out on what could have been, or what once was.

Entwined with this anxiety is a misplaced conviction that bottles age toward a momentary peak, then drop away into oblivion. Opening a bottle at the wrong time, many believe, risks missing that special moment. Too often, I've seen people unable to enjoy an otherwise delicious bottle of wine because they have convinced themselves that they missed the peak.

Determining which bottles to age and when to open them is among the most puzzling aspects of wine. Misunderstandings can cause misery. The aging question just adds one more layer of doubt to a subject with a seemingly endless capacity to induce angst in otherwise confident people. Every day brings numerous possible pitfalls.

Did I pick the wrong wine? Did I pay too much? Did I choose a bad producer? Did I serve it with the wrong food? In the wrong glass? Maybe I should have decanted it? Or not?

Here is the good news about aging wine: Regardless of what many people assume, there is no single right time to open any particular bottle. Whenever you decide to drink a wine is the right time. If you go about it the right way, it's hard to make a mistake.

First, it's important to understand that wine does not age toward an apogee of development, then drop off. Bottles that can improve with aging tend to move along a gentle arc, during which they will offer many delicious expressions, from youthful exuberance to middle-age complexity to eventual fragility.

Which stage you prefer depends on the particular wine and, especially, your own taste.

It used to be said that the British adored the character of well-aged Champagne in which the bubbles, perhaps aggressive in youth, had softened to a gentle fizz, and the flavors had opened into toasty complexity, perhaps with a bare touch of caramel. Biscuity, as the Brits like to say.

By contrast, the French were said to prefer Champagne young and lively, full of energy and primary flavors.

These are broad generalizations, of course. The point is that the best time to open a bottle is subjective. The trick is getting to know your own preferences, which takes a bit of time and effort.

One good method is to buy multiple bottles of an age-worthy wine. A case is great, but six is plenty. Then you wait, sometimes for a long time. Open a bottle in two years, a second in five. Note the path of the evolution and decide which stage you prefer.

Years ago, before prices soared, I bought six bottles of Louis Jadot Clos St.-Jacques 2002, an excellent premier cru Gevrey-Chambertin. I opened a bottle in 2007, and it was way too young, offering only the barest hint of what it might be. Drinking it was like being confined to only the first paragraph of a great book.

If that had been my only bottle, I might have been despondent. Aging one bottle of a wine is a risky proposition, like putting all your money into a single stock. With multiple bottles, your bets are hedged. Opening one bottle too early becomes useful information rather than a source of despair.

It was almost 10 years before I opened the second bottle, but wow, was it delicious, deep and complex yet still youthful. This wine has a long way to go, and I'm delighted to have four bottles left.

If you do plan to age wine, it's important to have proper storage. A cool, dark cellar, free of vibrations, is ideal. So is a million dollars to fill the cellar.

Most of us will have to survive with something less than ideal. Wine refrigerators are one solution. Good ones are worthwhile investments, though I have yet to meet anybody who believed that their refrigerator was big enough.

If you have a cellar, but it doesn't keep the ideal 55 degrees year round, fear not. Temperature variation is not terrible, as long as it does not get too warm. Except for very old vintages, wine tends to be sturdier than we think.

No matter how you store bottles, wine will occasionally find a way to fail you. A bottle might be corked, otherwise flawed or simply disappoint. Your annoyance level will rise in proportion to your patience and the size of your investment. Sadly, it comes with the territory.

The evolutionary path a bottle will take varies, depending on the type of wine, the style of the producer and the conditions of the vintage.

Wines like the finest Bordeaux, Burgundy and Barolo have a long arc of evolution. For their first 10 years, their potential for pleasure may be locked down underneath impenetrable tannins.

But these famously long-lived bottles are not the only ones worthy of aging. For years, people have recommended drinking Beaujolais and Muscadet very young. These wines, it was said, had no capacity to age.

This was the conventional wisdom, at least, when much of the Beaujolais and Muscadet was made cheaply for mass consumption. With all the processing these wines received, the wines' vital life forces were stripped away. Of course, they needed to be drunk young. With more time, they fell apart.

We now know, however, that if made conscientiously with minimal manipulation, even those wines thought not to age can surprise with their capacity to evolve. The propulsive vivacity of young Muscadet turns broad and deep over the years, no longer as incisive but more complex.

I don't dislike aged Muscadet: It can be wonderful, and some people like it better that way. But I've concluded that I prefer it younger.

I love young Beaujolais, too. But I recently opened a bottle of Daniel Bouland Morgon Vieilles Vignes 2005, and it was beautiful, silken and earthy, with an aroma of violets. I haven't had this wine in maybe 10 years, so I don't know what I missed along the way, but it sure is good now.

One of the great joys of wine used to be well-aged white Burgundy. It was said often that white Burgundy aged better than red. But that was before the late 1990s, when bottles of white Burgundy began prematurely oxidizing on a regular basis. Countless white Burgundy fans have had the unpleasant experience of eagerly anticipating a great bottle, only to pour out a cider-colored oxidized disappointment.

While strides have been taken, the problem has not been entirely eradicated. Far from every bottle is affected. But enough have been that I, like many other people, have cultivated a taste for fresh, young white Burgundy instead.

While I believe that most wines with the capacity to age will offer many points of pleasure along their journey, some mysteries remain. For me, one is the white wines of the Rhône Valley.

In their youth, they can be vivacious and floral, with a pleasant mineral edge. When they are older, say, 10 years old for a St.-Joseph and 20 years for a Hermitage, they can be gorgeous and, in the case of Hermitage, transcendent. In between? Too often, I've had white Rhônes that just seemed dull, as if they were cocooned or hibernating.

This transitional time between energetic youth and mature complexity is sometimes called a dumb phase. It's an irritating notion because it's difficult to know when it begins and ends. But it's also reassuring, as it indicates that the wine is alive and not a denatured, shelf-stable beverage. Luckily, I don't see this in too many other wines nowadays.

Perhaps more difficult than knowing when to open a bottle is initially judging its aging potential. Track records help to form general estimates.Aging estimates for wine genres are not hard to find on the internet or in wine textbooks.

For individual bottles, people often share their personal experiences on crowdsourced sites like cellartracker.com. You know a young Barolo or Barbaresco will need time. How much depends on your taste, the style of the producer and the quality of the vintage.

Other wines, eminently capable of aging — like the chenin blancs and cabernet francs of the Loire Valley, the reds of Mount Etna and blaufränkisches of the Burgenland, to say nothing of well-made rosés and sherries — require more intuitive guidance.

The structure, provided by tannins or acidity or both, and concentration, indicated by density of flavor, are the most obvious signs that a wine has what it takes to age. Yet just as important, if not more so, is balance, the sense that all the elements are there in proper proportion.

The issue of balance can sometimes call into question the proclamations of experts, and the ultimate importance of aging.

Certain vintages deemed great, like 2000 Bordeaux and 2005 Burgundy, have yet, in my estimation, to offer much pleasure. Both are concentrated and powerful, but a sense of equilibrium has often been missing in bottles I have tried.

Meanwhile, the 2001 and 2008 Bordeaux vintages, and the 2007 Burgundy, thought to be lesser vintages, have been delightful. Will they still be good in 2050, by which time future generations may be astounded by the 2000 Bordeaux and the 2005 Burgundy? Perhaps.

I'm not sure I'll be around to judge. But I'm pretty sure I will have had many happy experiences with so-called lesser vintages in the meantime.

Tips for Finding a Bottle With Legs

Tips for Finding a Bottle With Legs

Knowing which wines to age is not always intuitive, but with a little experience (and a modest bit of research), you can identify good candidates.

Historically great wines Burgundy, Barolo and Bordeaux are obviously age-worthy, but not equally so. Vintage conditions are crucial, and so is the style of each producer. The internet and guides like Hugh Johnson's annual Pocket Wine Book offer good general estimates by vintage of aging capabilities.

Carefully produced wines As a general rule, the more processing a wine receives in production, the less sinew it has to age and evolve. As is so often the case, a good wine merchant with an attentive staff can offer guidance about particular bottles.

Whites Rieslings, both dry and sweet, often age beautifully. So do many chenin blancs and chardonnays. It depends on the intent and methods of the producers.

Alcohol content Alcohol levels are sometimes meaningful, but not always. An unusually high level might indicate a wine out of balance. A pinot noir, for example, with 15 percent alcohol rather than the more typical 12 to 14 percent, might indicate a wine made from overripe grapes. But a different wine, like a zinfandel, might be more balanced at 14.5 percent.

Price It is sometimes a good indicator, but only when you are comparing a bottle within its genre. A $25 Chianti Classico is likely to age better than a $10 bottle. But the price equation does not always work. I've had $100 Napa cabernets that aged far better than more extravagantly priced Napa cult wines.

Wines that shouldn't be aged Mass-produced, processed wines are made to drink as is. Similarly, artisanally produced, thirst-quenching wines, sometimes called by the French phrase vins de soif, are made to offer immediate pleasure. They, too, will not get better with age.

The very best way to determine which wines to age is trial and error. Have no fear. Do you like young grüner veltliners? Put a couple of good bottles away for three or four years and see if you like the result. Try it with Beaujolais, too, or a good New York State cabernet franc. Experimentation is crucial, but sadly, time will not speed up for earlier results.

© 2018 THE NEW YORK TIMES.