Neighborhood Watch: Whittier-Phillips, Minneapolis

Cities change. That's what makes them beautiful, living, vital co-creations of the people who live there. This truism of course applies to Minneapolis, the city I've called home for 20 years.

Here are some things I love about Minneapolis: the spirit of collectivism (I wish you could see all the neighbors come out on a winter day to help drivers stuck in the snow); the parks (seven years ago the Trust for Public Lands started ranking the best park systems in America, and six times since then Minneapolis has been number one); the proliferation of what urban sociologist Ray Oldenburg dubbed third places, or public spaces on neutral ground, like theaters (we have the most theater seats per capita in the country) and public libraries (our main one is 350,000 square feet).

But cities can also dramatically reshape the perspectives of their own longtime residents. I never considered, for instance, how much of what I love about present-day Minneapolis has roots in Scandinavian design. It's easy enough to see where the Scandinavian influence in Minneapolis comes from—our founding population included likely the largest Scandinavian community of any major American city. When northern Europe was suffering 19th-and-early-20th century farming crises, one of the quickest paths to the US was to travel as far as Chicago by boat then take an overland route onward to Minneapolis. Today migrants from from Mexico, Central America, and East Africa, as well as the students, artists, cultural influencers, and social justice–minded folks likewise drawn to the area, increasingly interact with this historical legacy.

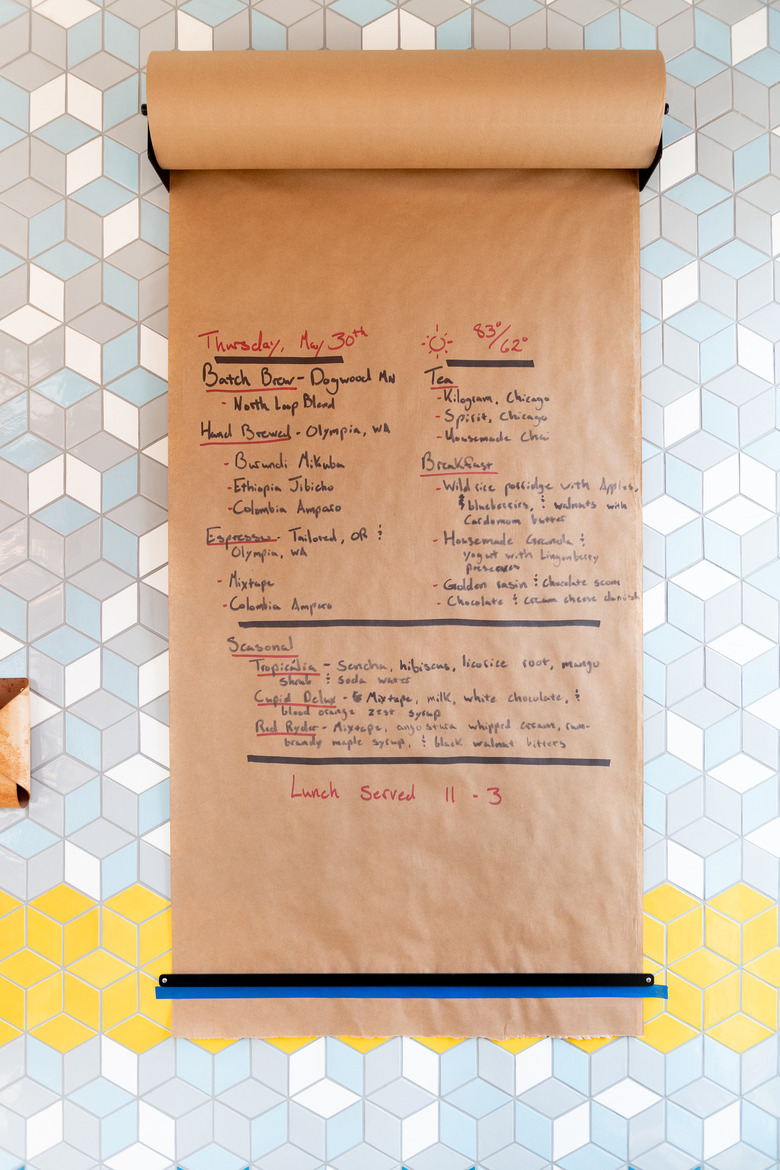

Whittier and Phillips, adjacent neighborhoods just south of Minneapolis' booming downtown, reflect the multifaceted nature of design in Minneapolis. The neighborhoods are home to leading Scandinavia-focused organizations like the American Swedish Institute (ASI) and Norway House, but they also operate alongside the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Victorian and Edwardian houses, brick four-plexes, and 1970s and 1980s apartment buildings. In hopes of distilling the Scandinavian contributions to our urban landscape, I convene a meeting with several of Whittier-Phillips's most significant design-focused leaders; we gather at ASI, which features plenty of traditional Scandinavian elements like leather-wrapped hand-rails to give chilly surfaces warmth and an all-day coffeeshop called Fika that offers that classic Scandinavian third place (as well as open-faced sandwiches and seriously tasty cardamom rolls).

"I was born in Oslo," explains Norway House Executive Director Christina Carleton. "I think what Scandinavian design means today is that idea of air, of not having a lot of clutter around on the walls. It's well-being. The idea that your quality of life has something to do with a space being well-functioning, simple, with clean lines."

I ask the assembled group, doesn't Scandinavian design have to be all pale wood and Eero Saarinen? No, they chuckle, blowing my mind by collectively suggesting that Minneapolis-founded-and-headquartered Target is an under-appreciated example of Scandinavian design in America, making good, functional design affordable and accessible.

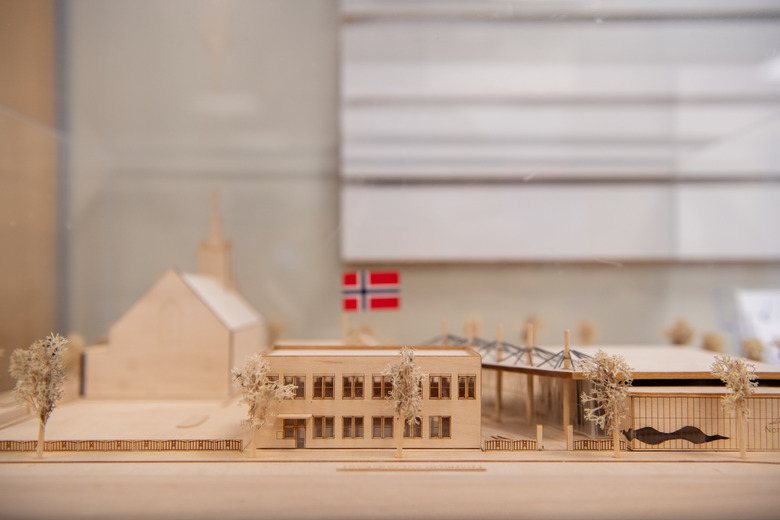

"I was born in Oslo," explains Norway House Executive Director Christina Carleton. "I think what Scandinavian design means today is that idea of air, of not having a lot of clutter around on the walls. It's well-being. The idea that your quality of life has something to do with a space being well-functioning, simple, with clean lines." Carleton spearheaded the campaign to expand Norway House a few years ago, and intentionally brought in Scandinavian design elements like big windows and an openness to the street in what ultimately became a bright-blue landmark on a main neighborhood thoroughfare. "People use our facilities from all over the community. An Ethiopian group meets every Monday for instance, to go through basic things, how to get a driver's license. We're a welcoming, convening space. That's very Scandinavian."

Bruce Karstadt, the President and CEO of ASI, points out that Scandinavian design influence often involves modeling different Scandinavian values in both the built world and in the community. For instance, Scandinavian green sustainability traditions are one reason that ASI is heated by 96 geothermal wells. Scandinavian welcoming traditions at least partially inform ASI activities like naturalization ceremonies, cross-community potlucks and smorgasbords, and community film premieres, where much of the multicultural fabric of the neighborhood is knit together. "There are a fair number of Somalis living here who have relatives in Sweden," notes Karstadt, explaining that Sweden and Minnesota welcomed about the same number of Somalis during the recent exodus from war-torn east Africa. "I serve as consul general for Sweden, so we have a fair amount of visa and visitation work facilitating contact between families here who have relatives in Sweden. We have a deep commitment to them." Staff at ASI have also been working with Somali cultural leaders to establish the Somali Museum of Minnesota, currently in a business center about a mile from ASI.

Peggy Korsmo-Kennon, ASI's Chief Operating Officer, says design in Whittier-Phillips is mainly dominated by themes of mixing old and new. "You might incorporate things that have been in your family for generations or you might find on the street or in an antique store with a basic simplicity ... It's the idea of migration and the migration of ideas. People aren't empty vessels when they arrive in a new place, they've brought ideas with them, and then they evolve responding to the environment, to the other people and cultures that they encounter." She suggests that a combination of these influences and a healthy dose of Scandinavian design, during a formative time in this community, laid the groundwork for modern Minneapolis. Woodworking, textiles, food, and storytelling are some of the key ASI projects that have drawn in people from every part of the city. "One of the things we're interested in is having people understand their heritage in relationship to others," Korsmo-Kennon observes. "We're in this weird time where people seem to want to argue that one culture is better than another; for me all of it is an opportunity to understand one another. Wonderful things happen when you mix it up."

"We're in this weird time where people seem to want to argue that one culture is better than another; for me all of it is an opportunity to understand one another. Wonderful things happen when you mix it up."— Peggy Korsmo-Kennon, ASI

Sensing that welcoming ethos in other areas of Whittier-Phillips, I also stop to visit neighborhood icon Anju Kataria, who runs the Whittier landmark Khazana. Khazana is an Edwardian house converted into an art gallery/library/jewelry shop/yoga center — you'll know it from the street by the antique British telephone box outside. Kataria greets me with hot tea, as she has so many folks coming in the front door over her 29 years importing art, textiles, and jewelry from around the world. "This is more like a space I just want people to come to be surrounded by beautiful things," Kataria tells me. "It's everything you want, and nothing you need." She tells me about a customer who uses items from her store to decorate, cutting them and putting them all around his house. "It's just the cutest house," Kataria recalls him saying. "He tells me: I live in Anju-land. Every room has pieces from here."

Kataria leads me on a tour of her finds-of-the-moment, recounting the stories of the artists behind each of the works on paper, raw silk blankets, cashmere curtains, and bright, grimacing masks. She also reveals a bit about her acquisition methods: "I try to stay away from anything synthetic. I want to meet the artist, but then I also go visit them to see if what they're saying [about the material] matches up with their story." Kataria spent her early childhood in India and moved to Minnesota to join her father, who ran a knick-knack and head shop in downtown Minneapolis called High Times. (He rented an apartment to Prince during the shooting of "Purple Rain.") Today Kataria connects artists all around the world with customers in Minneapolis. Echoing the sentiments of the Norway House and ASI leaders, Kataria tells me that Whittier and Phillips are open, artistic neighborhoods, and that she wanted this to be reflected at Khazana: "People from all walks can walk in here; there are no criteria," she says. "I wanted everyone to come in and be comfortable."

"I try to stay away from anything synthetic. I want to meet the artist, but then I also go visit them to see if what they're saying [about the material] matches up with their story."— Anju Kataria

As Kataria and I say our goodbyes, I zip over to "Eat Street," the roughly eight-block run of the Twin Cities' most densely populated restaurant row, to consider the connections between these neighborhoods, northern Europe, and so many other corners of the globe. There's no Scandinavian restaurant in this run per se — instead, I can walk out my door and in a few minutes get terrific fast Vietnamese food at a number of spots including Quang Deli, Caravelle, and Pho Tau Bay. I can get phenomenal jerk chicken from the Trinidadian specialty shop Harry Sifngh's or the Jamaican bar, restaurant, and music venue Pimento Jamaican Kitchen. There's fresh-from-Germany beers at Black Forest, just-roasted coffee at Spyhouse, rockabilly-glamour-girl donuts at Glam Doll, coal-oven pizza at Black Sheep, and one of those cute places that serves cakes in mason jars called The Copper Hen.

I then think of the words of Eric Dayton, who owns one of the state's most design-forward shops, Askov-Finlayson, and the restaurants, Bachelor Farmer Café and The Bachelor Farmer. While at first glance his café can seem particularly Scandinavian in its design, with its color palette of white and wood and warm blues, Dayton says any Scandinavian influence should by now be read as Minneapolis' own. "You can look at Blu Dot furniture and say, that's clean, that's modern, there's a sense of humor, a sense of whimsy, you can trace that to Scandinavian design, but to me that's Minneapolis design," says Dayton. "Color and wood. I think those are things that make sense here for a lot of the same reasons they make sense in Scandinavia ... with our long, dark, cold winters, color is a part of maintaining optimism, probably here and there for the same reasons."

"Color and wood. I think those are things that make sense here for a lot of the same reasons they make sense in Scandinavia...with our long, dark, cold winters, color is a part of maintaining optimism, probably here and there for the same reasons." — Eric Dayton

Turning to the future of design in this particular pocket of Minneapolis, I hear that it is a time of cross-pollination and mixing. "There was the Minneapolis sound," notes Dayton, of the music made famous by Prince and his local peers and available at the iconic record stores in the neighborhood, like Cheapo (a used-record-and-CD specialist, open since 1972) and Electric Fetus (founded 1968, and one of the top ten record stores in America according to Rolling Stone.) "I hope we can find our Minneapolis sound whether it's in design, food, or drink. That we become known for our voice." Bruce Karstadt said he was thinking about the importance of buildings that were three things all at once: functional, beautiful, and made of such quality that people would want to invest in maintaining them. "I like that idea of a high-quality city." Christina Carleton noted that lately she's noticed people staying in these close-downtown neighborhoods even after they have kids. "They're making it work in a small environment, and that's very Scandinavian." Peggy Korsmo-Kennon talked about how powerful it has been for different elders in the Scandinavian community to engage in storytelling and sharing with kids from nearby schools, "I think this last time there were people from 12 different countries," her face lighting up with a giant smile at the memory.

I step back out onto the streets I have walked for 20 years with fresh eyes for Whittier and Phillips. Was the reason so many Victorian homes were still standing and so well loved because they had been built with quality to begin with? Obviously, yes. Was the reason I could go to maybe 50 restaurants and find 50 nations interacting on Eat Street something rooted in the Scandinavian past I'd scarcely thought to think was there? It was the first time I ever thought to consider that Scandinavian design was more than classic teak dining room sets and wonderful clean lines...

Cities do indeed change—but good city design can have ramifications for something close to forever.

1. Credits

Images: Chad Holder

Words: Dara Moskowitz Grumdahl