The Lazy Susan: Who Was Susan, And Why Was She So Lazy?

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

"8.50 forever seems an impossibly low wage for a good servant," read a 1917 advertisement in Vanity Fair. "And yet here you are; Lazy Susan, the cleverest waitress in the world, at your service!"

The Lazy Susan — a round, rotating tray meant to sit on a table or counter and allow multiple diners to access food without having to pass dishes — predates the aforementioned ad, but historians can't agree where the name actually came from. Some credit Thomas Jefferson with the invention and say he named it after his daughter, though there isn't a Susan among them. Others insist the Lazy Susan was a device created by the Oneida Community, who in the mid-19th century retreated from society in order to build a utopia in which love was free and chores were evenly distributed, while a 1916 cookbook notes the Lazy Susan's popularity among German housewives.

Why was the Lazy Susan invented?

Why was the Lazy Susan invented?

What's clear, if the Lazy Susan's origins are not, is that the device is one of many such inventions meant to bring technology into the home for the express purpose of replacing servants.

In the 18th century and early 19th century, the Lazy Susan would have been known, like a number of other objects, as a "dumbwaiter." We think of dumbwaiters now as, essentially, food elevators, but at one point it was a catchall term for kitchen tools meant to do tasks usually performed by servants. For the wealthy of the time, servants were a constant problem — if they weren't eavesdropping on a private dinner conversation, they were slow, or prone to dropping things, or too expensive. In 1755, English poet Christopher Smart penned "Mrs. Abigail and the Dumb Waiter," in which a servant laments all the work she's lost to the invention:

As Abigail one day was scow'ring,

From chair to chair she past along,

Without soliloquy or song;

Content, in humdrum mood, t'adjust

Her matters to disperse the dust. —

Thus plodded on the sullen fair,

'Till a Dumb-Waiter claim'd her care;

She then in rage, with shrill salute,

Bespoke the inoffensive mute: —

"Thou stupid tool of vapourish asses,

With thy brown shelves for pots and glasses;

Thou foreign whirligigg, for whom

US honest folks must quit the room;

Who patented the Lazy Susan?

Who patented the Lazy Susan?

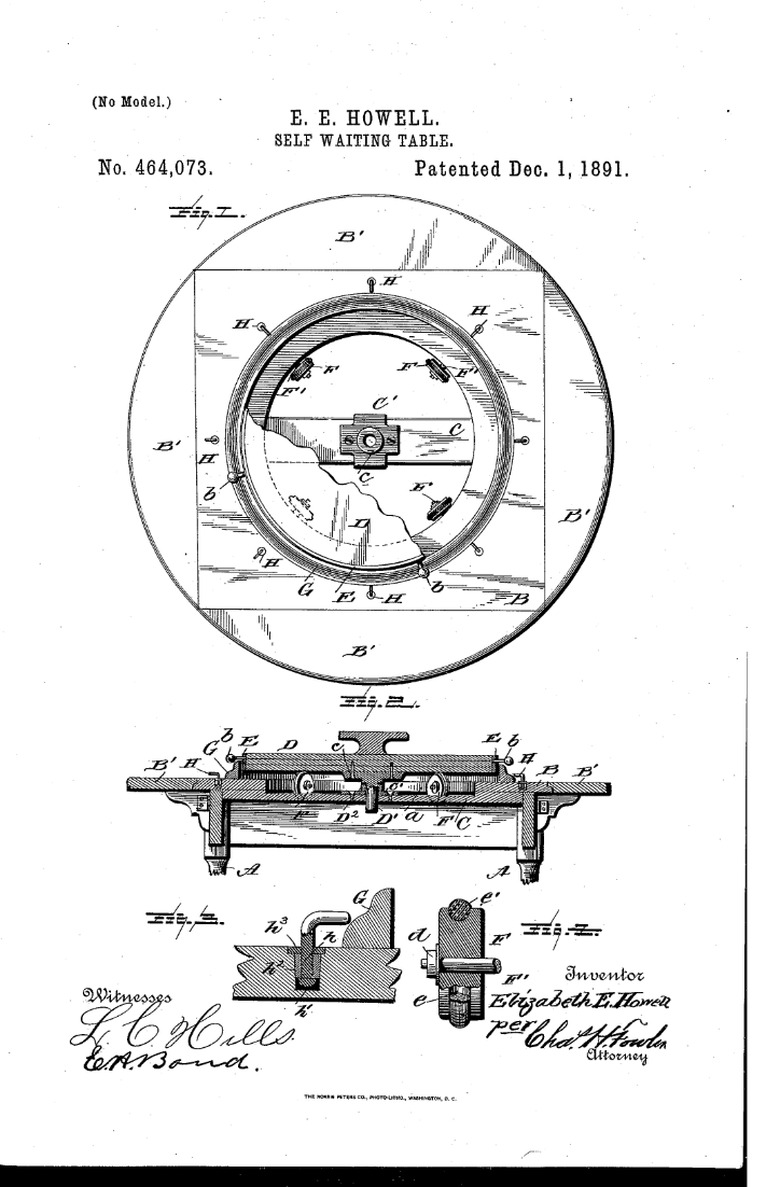

In 1891, an American woman named Elizabeth Howell filed a patent in Missouri for a "Self Waiting Table" that purported to be better at catching crumbs than other rotating servers, and her design was the basis for the majority of Lazy Susans produced in the early 1900s.

Why is it called a "Lazy Susan"?

Why is it called a "Lazy Susan"?

But how do we get from Abigail to Susan? In The Server: A Media History from the Present to the Baroque, historian Markus Krajewski suggests that the name Susan "harks back to a collective term quite commonly used in 18th-century England." By the early 1900s, the name "Lazy Susan" seems to have stuck, and ads like the one in Vanity Fair encouraged shoppers to consider Susan a replacement for servants. The timing couldn't have been better — Krajewski points out that by the First World War only the richest of the rich could afford live-in, full-time help, and the Lazy Susan then becomes a real harbinger of changes to come. As the 20th century marched on, household helpers like vacuum cleaners, dishwashers, electric laundry machines, and microwaves would move into kitchens and dining rooms, allowing households to run on less and less manpower each year.

The Lazy Susan itself wasn't immune to being replaced, though some of them are still highly prized. In 2013 a Lazy Susan dating to the 19th century sold at Christie's for more than $3,000 — a bit higher than $8.50, after all.