The Artist Studio In Brooklyn That Almost Didn't Exist

It was either the funeral home, or give up the ghost entirely. "I had a really bad show," explains designer Hana Getachew from her textile studio in Brooklyn, New York. "I put so much effort into it — all my heart and soul — and nobody stopped, nobody chatted." The founder of Bolé Road Textiles had positive experiences showing her collections before, but this time left her without a single conversation on the books — let alone a connection or a sale.

"I was like, 'OK, so what are you going to do?'" Getachew asked herself the hard questions that bob in the mind of anyone bootstrapping a business: Are you going to back down? Are you going to say 'this is it'? "And I was like, 'F-that I'm doubling down.'"

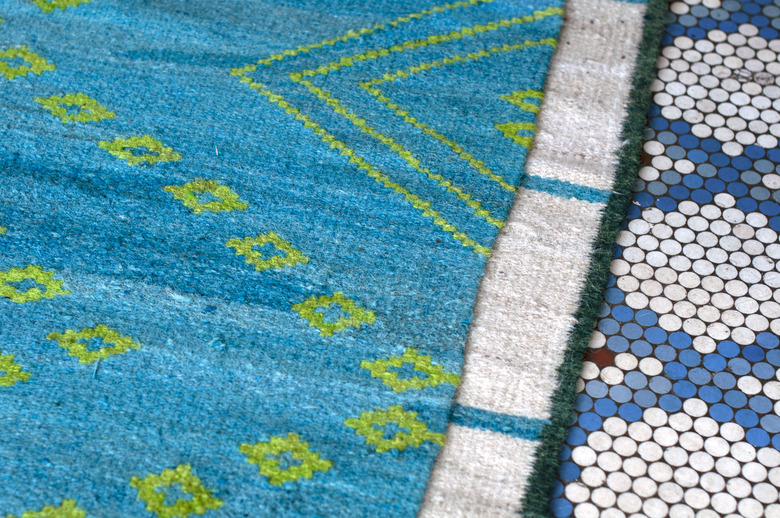

The next week, Getachew saw a "for rent" sign on what she learned was a former funeral home in Gowanus, a neighborhood in Brooklyn. She decided it was the kind of space where she would bring her business to life. "I think it's a combination of the floors — which bring a little bit of whimsy and playfulness — and the white walls, which help me think about creating." But, if she's being honest, she chose it mostly for the floors. "My biggest worry and my biggest love," she says of the brown and blue tiles that line the bottom of her studio. The strong aesthetic became instant inspiration for Getachew — the color scheme found a home in her collection and wove its way into little details around her studio and life. "A big part of the design process is being influenced by what you see — so much of it's the subconscious brain."

Getachew treats her space like "a neutral envelope," as she puts it. "It's like having a nice clean canvas to create," she says. She typically lets her products and furniture take center stage in the studio by keeping the space almost entirely white — a sort of Pavlovian preference she developed early on in college. Getachew recounts her days as a fine arts major like she's watching it project onto a screen only she can see. Part of her program included time spent painting in a 200-year-old building, in which the top floor had been gutted and turned into an all-white studio, flooded with natural light from skylights and the floors weathered from canvases. "I had no idea what it meant to be an artist," she says. "I just knew when I first walked into that space that this is what I wanted." She went on to get a degree in interior design, then become associate principal at an architecture firm in New York City, where she designed flagship stores and commercial interiors, before moving on to consult with a small, women-owned firm. "It was actually the first time I had worked under a woman, and she was a woman of color, which meant a lot to me," she says.

As a woman of color herself, Getachew brings the spirit of her birthplace of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, into her studio not only with her contemporary take on traditional motifs, but she also incorporates her diaspora culture by the way she interacts with people outside of the space. "I have this invisible relationship with the passers by that I don't know, that I don't meet," she says. "Sure, I have my clients that come in, are interested in textiles, but what about everyone else?"

Getachew explains there is a trade-off to leaving her home country — where the fabrics are handwoven by local artisans — when it comes to the concept of "community" in Ethiopia. "There's no comparison," she says about living in the States. "The relationships my parents have [in Ethiopia] are almost indescribable — there's a love and attachment between both family and friends."

Around the same time she was learning what it meant to be a capital-A artist, Getachew took a summer trip to Ethiopia. She traveled alone by bus to and from museums to conduct research while in college. One day, she found herself caught in a downpour when she heard voices coming from inside a dark kiosk telling her come here, come here, come here. Getachew took shelter from the storm, while sipping tea with strangers, per their request. Of course, when she went to leave, they wouldn't let her pay for the tea. "That really kind of captures like Ethiopian mindset and spirit," she says.

Like her rainy-day friends, back home Getachew hosts traditional coffee ceremonies in her studio along with an Ethiopian cafe owner she knows in the borough. "I'm a Brooklynite," she says. "It's what I really know at this point — I do this to build a sense of community with my immediate neighbors," she says of the celebration.

"It's important to have spaces that nourish and restore you, and this space does that for me," she says. As part of her self-care practice, Getachew set up a permanent coffee corner and gifts herself fresh flowers on Mondays, though her chosen reality comes at a cost. Having a studio meant eliminating luxuries like a personal trainer or eating lunch out. "It's about deciding what is important," she says.

"When you're a business owner, you kind of do everything, and you spread yourself really thin. But once you're forced to focus on what's really important, you end up doing the things that matter most, it makes you hyper-efficient," she says. "I was having one of those business moments where you really doubt everything and then I came to a crossroads." Her risk to take on a studio paid off, as stockists like Goop and One Kings Lane carry her collections.

"This space brings me delight and joy — and that's the goal that I'm trying to capture for my clients," she says with the same far-off eyes as when she talks about her other muses — white walls, funky floors, Addis Ababa, and humankind. "I want them to be able to say, 'Oh yeah, this is the feeling I was going for.'" She meditates on all of this, asking herself simple questions as markers of true success: Do I still have clients that appreciate my collections? Am I still in love with what I'm doing?

For Getachew, in her funeral home turned home away from home, it's either be afraid of the answer or forever be haunted by the unknown.

"If we wouldn't have left Ethiopia, I wouldn't have this business. Or who knows — maybe I would. We have our own paths, our own journeys," she says.