The New Hometeliers: Colorado Lodge

The story behind the Colorado Lodge in Big Bear is as much about friendship as it is about design.

Six years ago, David Godshall, principal of the landscape architecture firm Terremoto, moved down the street from Marcus McInerney, the developer and designer behind sheet/rockLA. They're maybe a couple hundred feet apart on a quiet hillside residential street in the heart of Echo Park, a rapidly gentrifying pocket of northeast Los Angeles once known for its gangs. "I think we met because you posted a picture of a cactus I planted, or something," Godshall says casually to McInerney over lunch. "We would just always see each other."

Rather quickly, it became apparent that the two had shared sensibilities. As Terremoto grew from a home office into larger and larger commercial spaces, sheet/rockLA at one point became a tenant — albeit briefly. "It means I had about four meetings there," McInerney laughs.

Yet they found other, more fruitful ways to collaborate. Their first official foray was Rosey Jones, a small lot subdivision on Rosemont Street, also in Echo Park, which sheet/rockLA was working on with Jerome Pelayo of Sunia Homes.

"I'm always trying to beg developers to prioritize landscape," says Godshall. "In small lot subdivisions they monolithically do not. But Marcus was game." The result was a group of seven modern, detached single-family homes, with thoughtful garden space rich with California native plants between.

"Have you been by there lately?" Godshall asks, casually. "It's pretty crazy and grown in."

Now, Godshall and McInerney's latest venture — the Colorado Lodge — brings them regularly to Big Bear, about 100 miles east and 6,700 feet high in the San Bernardino Mountains of Southern California. It's equal parts business venture and — if you're an architect or designer, at least — what might constitute play.

"Marcus went in and stripped it down until it was nothing. The interiors are essentially completely new — it's almost like an archeological remnant"-David Godshall

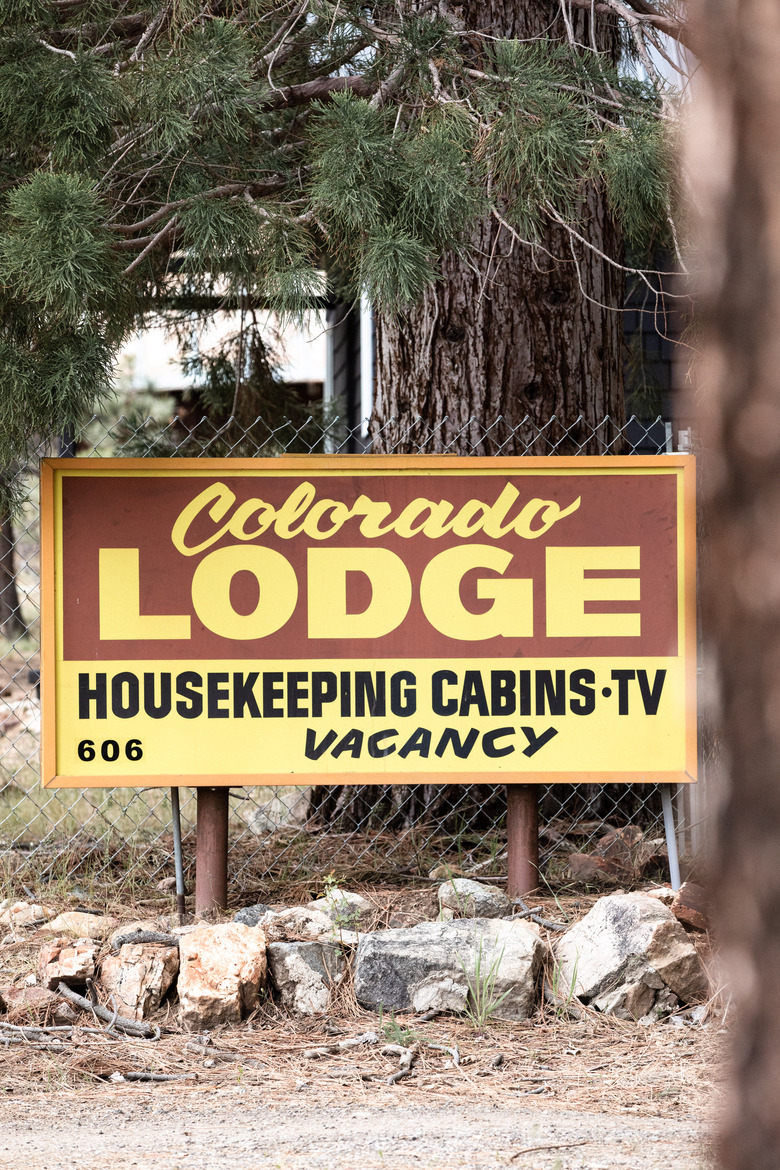

For decades, the Colorado Lodge was just another set of unassuming housekeeping cabins and a granny flat on two parcels on a side street, perfectly situated between The Village and Snow Summit. The name — and the sign, still original — dates back to the 1930s. And the well-worn charm is all there — little placards identify each cabin with impossibly quaint throwback names like "O-So-E-Ze" and "Stay Awhile," fashioned from twigs and wired by hand.

A couple — Tom and Ethel Burns — were the original resident-owners. After Ethel passed in the early '80s, Colorado Lodge slipped into a familiar kind of vacation-town disrepair, with long-term tenants and dust-riddled vacancies. When McInerney happened upon the property, while up snowboarding back in the winter of 2016, it wasn't yet on the market — it was being sold via probate for little more than land value.

"They were like, Tear this crap down," McInerney says. But he immediately saw potential.

Shortly before he found the property, McInerney had unearthed a sticky note he had written to himself about five years prior that read, "Look for a place to build a bunch of small black A-frames in Big Bear."

And there it was.

Godshall was on board immediately.

Together, with two other investors, they began to riff on their take on mountain modern.

The initial high-concept treatment embraced the nature inherent to their spot on Jeffries Road, with its towering pines, dry creek bed dotted with boulders, and a fine layer of pine needles across the property, as well as different, more abstract concepts of gathering spaces. The interiors — led by Godshall's wife, Lauren Jordan, the designer behind the LA outpost of The Goods Mart, on Sunset Boulevard in Silver Lake — were variations on a theme, each open and modern, and yet, with plywood surfaces throughout, referencing the nature just outside. "You're in the forest, there are these giant trees, and then you enter into the cabin in which all the surfaces are then referencing wood as well, just manifest in a totally different way," Godshall explains. Even the patterned linoleum is meant to reference the forest floor.

"Once we had initial architectural concept," says Godshall, "Marcus ran with it." Although they worked with local contractors at various points, McInerney drove up weekly to help keep a tight rein on the construction.

Each cabin they've touched had to be completely gutted. "Marcus went in and stripped it down until it was nothing. The interiors are essentially completely new," says Godshall — and that includes much of the framing. "It's almost like an archeological remnant." Then, Cinderella-like, a coat of black Pratt & Lambert paint over the original cedar shingles gave the cabin its new, modern identity — the popcorn ceilings demoed to reveal peaked roof lines and exposed beams, cheap wood paneling giving way to Baltic birch, a lofted sleeping nook here, a Japanese-esque sleeping platform there.

The cabins — one and two bedrooms — are all outfitted with a simple kitchen, custom cabinets and shelving, and a washer-dryer combo (a must for McInerney, who understands the snowboarders they host), as well as the kind of minimal, modern furniture and wry accessories one might expect of any well-appointed Airbnb back on the east side of LA — not unlike one of McInerney's other projects The Kent, chicly furnished apartments off Sunset Boulevard in Echo Park. There's none of the requisite knotty pine or carved bears in sight. Instead, you get a tongue-in-cheek bear print by Becca Tapert, a photographer and designer out of Seattle — or a bubblegum pink erupting volcano.

When Colorado Lodge officially opened to the public, in December 2018, five of the nine buildings had been renovated — the new coexisting with the old, in a pretty fascinating way. A sneak peek into two of the original cabins — still that iconic shade of Big Bear red — reveals curled linoleum, low slung ceilings, old bed springs, even a handwritten notice about check out time and late fees in what must have been Ethel Burns' perfect cursive. There's an extra-large three- or four-bedroom cabin they plan to remake into a more communal space — the type of kitchen, porch, and living area that would allow you to host, say, a Thanksgiving meal, if you'd rented several of the other cabins on the property. The old trash incinerator remains on-site — begging to be turned into a roaring pizza oven. Given the constant state of creative flux, the back and forth between McInerney and Godshall, it very well could be.

But this, Colorado Lodge's first summer, is all about the landscape. "I officially want to start championing it as a Terremoto project," says Godshall — and his ideas are many.

Thus far, new projects include minimalist walkways and decks that create a type of conversation between the cabins nearest the hot tub and the dry creek, as well as sleep barriers that feature abstract shapes cut from marine-grade plywood, meant to add to the ever-changing mottled shade on the property — but also block the view of parked cars and occasional traffic that reminds you, somehow, that you're still in the middle of a city. It's their signature approach — practical in nature, made of accessible materials put together in thoughtful, minimalist ways.

"We think it's kind of cool that potentially every time a person goes," says Godshall, "it will be different."

Godshall and McInerney discuss stargazing decks, simple outdoor huts, and rough-hewn logs to crisscross the creek bed. McInerney is experimenting with lighting — giant, red LED floodlights, shooting straight up into the tree canopy.

"We want to get into weird territory at the lodge," Godshall laughs.

It's all casually iterative. While McInerney talks about the snowboarders who've come to stay not necessarily for the aesthetic but to be close to the mountain, Godshall wonders out loud if they could create some kind of half pipe. "Oh yeah, the snowplow guys, they have to put it somewhere," McInerney muses. "It's something we should think about," Godshall says.

That small interchange is at the heart of what's happening in the background as the Colorado Lodge itself grows and changes — a hum of ideas, creative exchange.

"When you're old, the best way to be friends with a person is to do projects with them — in our line of work, at least," says Godshall. "It's our excuse to get to spend time together."

Time — which, as their respective businesses have matured, comes increasingly at a premium.

McInerney has other design-minded Airbnbs — Night Moves, in Joshua Tree, and The Kent, both of which are managed by other people — as well as the docket for sheet/rockLA, which, serendipitously, includes a new project not unlike Colorado Lodge — redeveloping seven existing bungalows, on almost 2 acres, in Glassell Park, just up the road from Echo Park. Terremoto, with offices now in LA and San Francisco, is flush with residential and idiosyncratic commercial landscape projects, and Godshall recently opened Plant Material, a sort of design-minded nursery, also in Glassell Park.

And all the while, McInerney manages the Colorado Lodge from the convenience of his phone. More so than his other Airbnbs, he's personally invested in the success of the property, answering every query, making right whatever's gone wrong. It's partially because the place is not yet complete — there are cabins still left to transform. And partially because of his own personal connection to Big Bear. His father got a 30-year lease on a U.S. Forest Service cabin high above the Big Bear Dam when McInerney was 8 — and he's been helping work on the cabin ever since. And McInerney's own son, nearly 12, has also taken up snowboarding. They get season passes, and even if the cabins are full, they can still slip into the original granny flat near the entrance. It's business and pleasure all mixed up in one.

In practical terms, what McInerney and Godshall are doing at Colorado Lodge isn't necessarily new — there are developers taking old properties and making them new again left and right. But their perspective, and their intent, is a new look for Big Bear, a new take on mountain living, and new ways to play with design. And it's evident everywhere on the property. It's in process. It's high-minded, and humble. In many ways, it's a project with no fixed ending — which makes it a process any guest can be part of. "We think it's kind of cool that potentially every time a person goes," says Godshall, "it will be different."

1. Credits

Words: Laura Lambert

Images: Stephen Paul