What Is A Shotgun House?

In August of 1903, a real estate advertisement appeared in the Atlanta-Journal Constitution:

"Two three-room houses near the railroad yards at Simpson St. crossing, rent $12 a month to good tenants who pay in advance; price $1,200 on terms or $100 cash, balance $15 a month; a combination of investment and savings bank: these are not shacks, but good shot-gun houses in good repair."

Anyone living in the American South would have instantly recognized the houses on offer. Since the turn of the 19th century, the shotgun house had come to be an integral part of the urban landscape in cities like New Orleans, Louisville, Atlanta, and Memphis, but their roots extend even farther in time — and place.

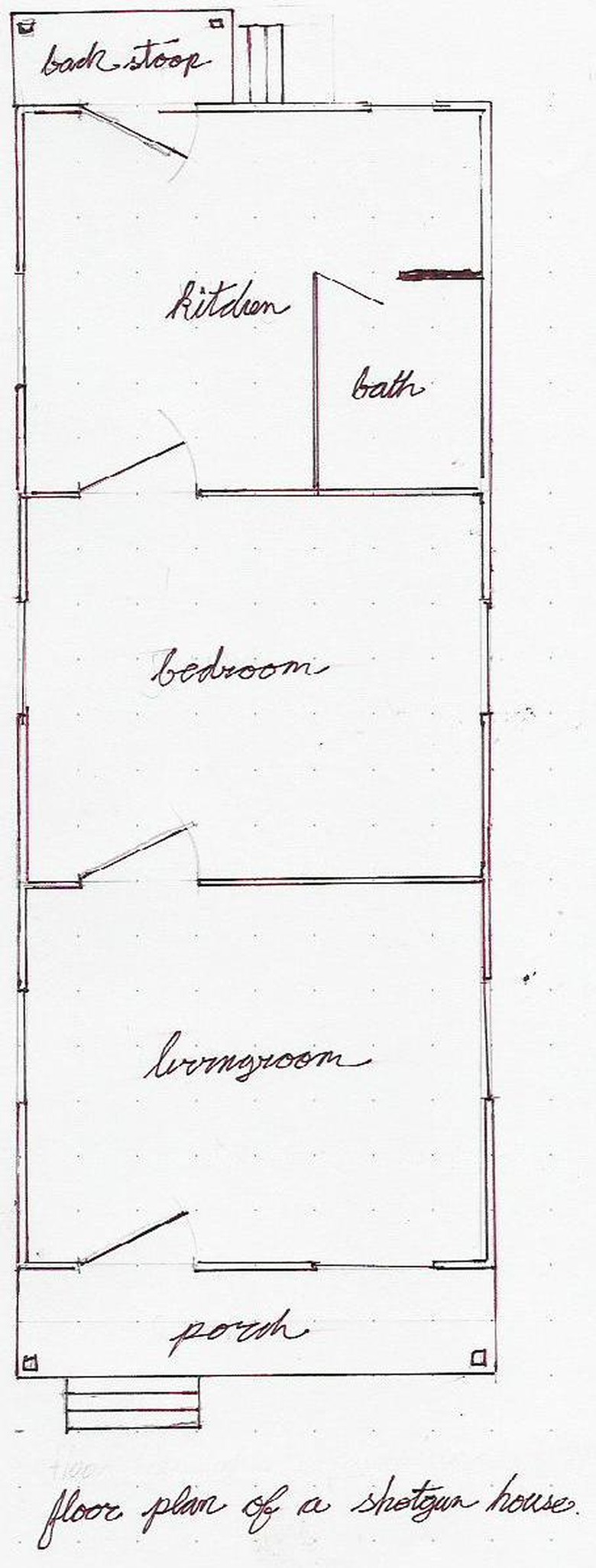

The architectural basics of the shotgun house are simple: rarely more than 12 feet wide (to accommodate small lots), a shotgun is a house in which one room is set directly behind the one before it, starting with the living room (the most public part of the house), sometimes moving onto a bedroom space (though for cost reasons plenty of shotgun houses initially had just two rooms) and ending with the kitchen. Many shotgun houses were originally constructed without plumbing, and a rear kitchen meant less distance people in the house would have had to carry water. You could, it's sometimes said, fire a shotgun through the front door and watch it go straight out the back. While many associate that notion with the naming of the shotgun house, historians in the late 20th century began to argue that the shotgun house comes directly from the migration of formerly enslaved Africans from Haiti to Southern U.S. cities in the early 1800s.

In The Shotgun House: An African Architectural Legacy, George Washington University professor of American Studies John Michael Vlach suggests that "shotgun" stems from "togun," a Yoruba word meaning "house" or "dwelling place." Vlach, a scholar of Black architecture in the antebellum United States, argues that the shotgun house represents the melange of style and culture that evolved as free Black people with limited resources adapted the housing types of their West African ancestors to coastal (and humid) cities like New Orleans, where building homes that were both inexpensive, compact, and easy to cool was of the utmost importance. The layout of the shotgun house encourages airflow even on the stillest of days; keeping the front door and the back door open ensures any breeze flows to all parts of the house.

Black Americans, Vlach points out, are often denied credit for their contributions to American architecture, especially when it comes to vernacular housing — not only did many Black people live in shotgun houses, they built them, too, pulling from other architectural trends as they emerged. That's why, according to architectural historians and preservationists, many shotgun houses boast details like gingerbread trim and even non-functioning columns.

By the 1920s and '30s, shotgun houses were considered low-income houses in most of the cities in which they appeared, and were an especially popular type of investment property — an investor might be able to purchase 10 or 20 shotgun houses in close proximity, and rent them out at a high markup due to the need of many lower-wage workers to secure housing close to downtown hubs.

But like many types of vernacular architecture in American cities, the shotgun house has, in the last few years, become especially appealing to would-be home buyers, a fact reflected in the number of shotguns that have been renovated and listed at high prices in Southern cities. In 2017, one Waco, Texas shotgun house got a makeover from the patron saints of renovation themselves, Chip and Joanna Gaines. After appearing on Fixer Upper, the home's owner listed the house for sale at a price of nearly $1 million.