What's Up With Movie Villains Living In Amazing Homes?

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In the new book, Lair: Radical Homes and Hideouts of Movie Villains, architect Chad Oppenheim wants to know: Why do bad guys live in good houses? It's one of those "wow" questions that most people have never really considered, but once it's out there, you can't help but think, "Yeah, why do they?"

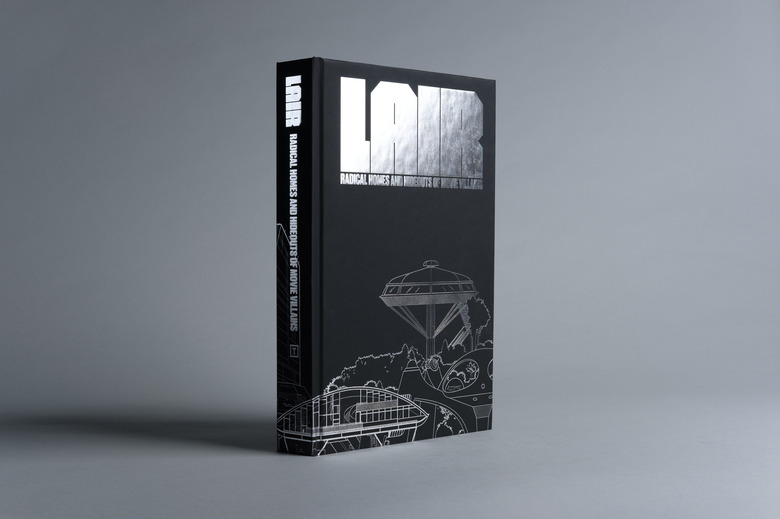

The hefty black-and-white book (which is admittedly ultra display-worthy) showcases architectural renderings of 15 classic movie-lairs (from The Spy Who Loved Me, Lethal Weapon 2, and Dr. Strangelove, to name a few), along with stills and commentary from architects. Nestled in between the lairs, you'll also find essays and interviews from a wide cast of insiders (director Michael Mann; Ralph Eggleston, art director on The Incredibles; Roger Christian, Star Wars set decorator). We sat down with Oppenheim to talk about the book and the role architecture plays in so many great movies.

Leonora Epstein, Hunker: As an architect, what inspired you to specifically research the homes of movie villains? Why not heroes or other characters?

Chad Oppenheim: The book kind of started many years ago. I grew up in New Jersey, in a town with a lot of mafia guys actually, believe it or not. And they always lived in really cool houses. But nevertheless, when I was very young, my father connected me to The Man with the Golden Gun, and it just blew my mind. It was the first time I ever saw a James Bond film and it just was an incredible moment, where I saw this evil villain's lair, which was in the rocky island cliff in Thailand. And his lair was built into the hillside and that really triggered it and it actually triggered me off to become an architect, because I was like, "Wow, this is really cool."

LE: So in compiling this book, what interior or architectural details did you find that movie villains have most in common in their lairs?

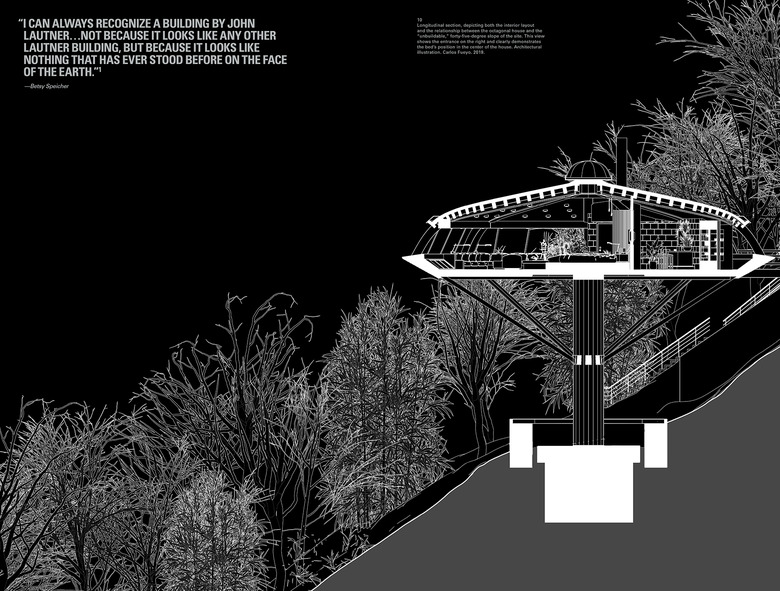

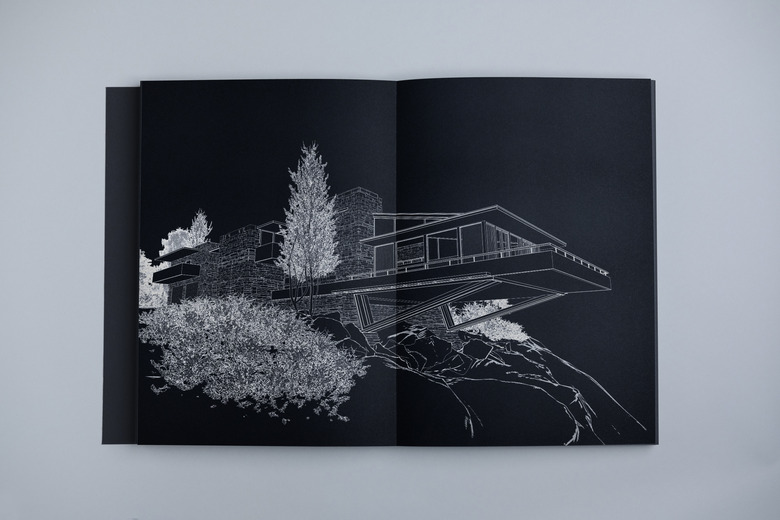

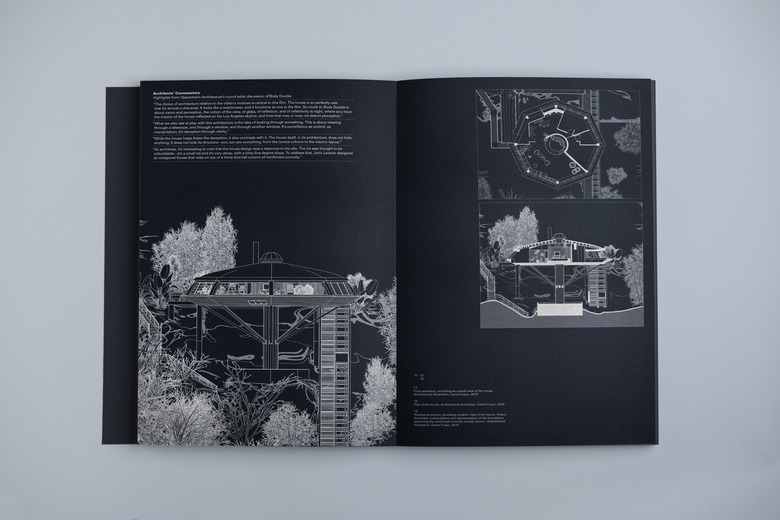

CO: I think what really got me excited, and I guess it resonates a lot with our work as architects, is this very dramatic relationship with nature. If you look at The Man with the Golden Gun, [the director] was inserting this architecture strangely in a delicate way into this very beautiful landscape. Because it's always a hideout, right? So it can't so visible. If you think about the Elrod House in Diamonds Are Forever, the way that that building actually brings in rocks from the site, it's very powerful. Lautner actually designed that house. So there's this a very connected notion of building in nature and oftentimes in a delicate way. If you look at Ex Machina, the billionaire antagonist has this house that's very delicately within this what's supposed to be Alaskan wilderness.

LE: Can we talk a bit about the interiors? I'm especially interested in some of the contradictions, like in The Spy Who Loved Me, he's living in this highly mechanized submarine, but then there's this old-world dining room kind of situation.

CO: Yeah. I think it was best [said] by one of the panelists [we had for a discussion of the book, who said]: "The outside is this kind of mechanized octopus and the inside is like Downton Abbey."

LE: Yes!

CO: It's kind of interesting, right? Because [in many films], even in The Man with the Golden Gun, there's a lot of domesticity going on. There's a lot architecture [that's] high-tech or bunker-like, but then there's this kind of domesticity. In that case, The Spy Who Loved Me, it's an almost gothic or baroque-level of kind of comfort ... I guess it also shows a bit of wealth and a bit of power ... [With Atlantis], I mean, that's kind of really an incredible statement. It's like, "Yeah, this thing has a fireplace, but I'm in a submarine."

LE: It's like, villains are never poor.

CO: Exactly. It's all very aspirational. It's like, "Wow, look at the way these guys live." [And yet] the hero, James Bond, he's homeless almost, right? He has Skyfall [Lodge] that shows up in movie number 18 or something, that it was his family's home. But in reality, the guy's homeless. I think you see it very strongly in Star Wars. Darth Vader has the ultimate weapons, the ultimate machinery to kill and destroy planets. The Death Star ... the evil emperor's machines and stations and everything, are phenomenal. But it's almost like this David and Goliath-type of scenario. Luke Skywalker comes from a farm. And the Millennium Falcon's a hunk of junk that could barely turn on when they needed it. But it gives it that tension that I think creates an interesting story.

LE: Totally. I think probably there's also something just in terms of having audiences feel more identified with heroes than villains and having a sort of American wealth complex at work here.

CO: Oh, yeah. For sure. And then interestingly enough, a lot of villains are oftentimes the more complex characters, as well. They believe what they're doing is correct. They've drank their own Kool-Aid. And a lot of times, the architecture and what they're doing is, in their minds, utopian.

LE: Sure, I mean, you can look at a lot of scary architecture in the world that was built out of quote-unquote utopian ideals.

CO: It goes back to a lot of the Third Reich's architecture, this architecture of propaganda. There's a [part] in the book about the production designers for Star Wars and they were very inspired by the Third Reich architecture. It was very powerful and dramatic. And you can see it in even the last Star Wars installment, where there's these big banners and flags.

LE: I think it's also really interesting, just continuing on this thread about juxtaposition and contradiction, what Joseph Rosa writes in the opening essay for your book — about the original intent of modernist homes being to encourage easier living, inviting nature in, attempting to form this new type of American idealism within the home ... and that being so contradictory in the context of these movies where modernist homes become backdrops for villainy.

CO: But these villains always want the better way of life. Look at the antagonist in Ex Machina: He believes he's playing God. He wants to create a new future, a new sentient being that will be better than human kind. So it kind of follows through, I think, with that notion of creating better places, creating better ways of life.

LE: I mean, that's a really good point. And it kind of makes me think, do you think that the reason that modernist homes never made the jump into becoming the American norm, is that there just aren't enough villains in society to live in those homes?

CO: Well, I don't know if that's the case ... but I think most people feel comfortable with traditional and conservative thoughts and conservative ways of life. I think you see modern architecture in interesting places, let's say in South America and other places where, they were basically starting new, starting fresh. So I think it really has a lot to do with this idea of comfort, of tradition, and not a lot of people want to rock the boat on that ... I mean, it's like, looking at the Capitol in Washington, DC., it's all copies of Greece, and visions of Rome and stuff like that.

LE: Last question: Architecturally speaking, how feasible would it be to build an evil headquarters inside a volcano?

CO: Yeah, there's definitely some really complicated challenges to deal with that. I mean, hopefully this volcano's dormant, although in The Incredibles, they were able to kind of control the active volcano, which I thought, The Incredibles kind of brings it all together, almost a greatest hits of these spy films and superhero genres. And they were able to create in harmony with the power of the volcano, right? The ultimate power of the earth: They were able to harness it.

Words: Leonora Epstein

Photos courtesy Tra Publishing