7 Black Architects Who Have Shaped Modern Architecture

If you have ever flown to or from Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), shopped at a Saks Fifth Avenue or the Mall of America, or visited Duke University, you've experienced the magnificent works of Black architects. They've contributed tremendously to the modern landscape and design of the United States and beyond. But Black architects have continually worked against the odds and rarely received due credit.

Many sources cite the findings of The Directory of African American Architects, which shows less than 2% of registered architects are African American. However, lack of visibility by no mean equates to lack of influence. We're taking a look at seven Black architects whose brilliant work continues to serve as a testament to talent outweighing constraints. This is just an introduction, and by no means exhaustive.

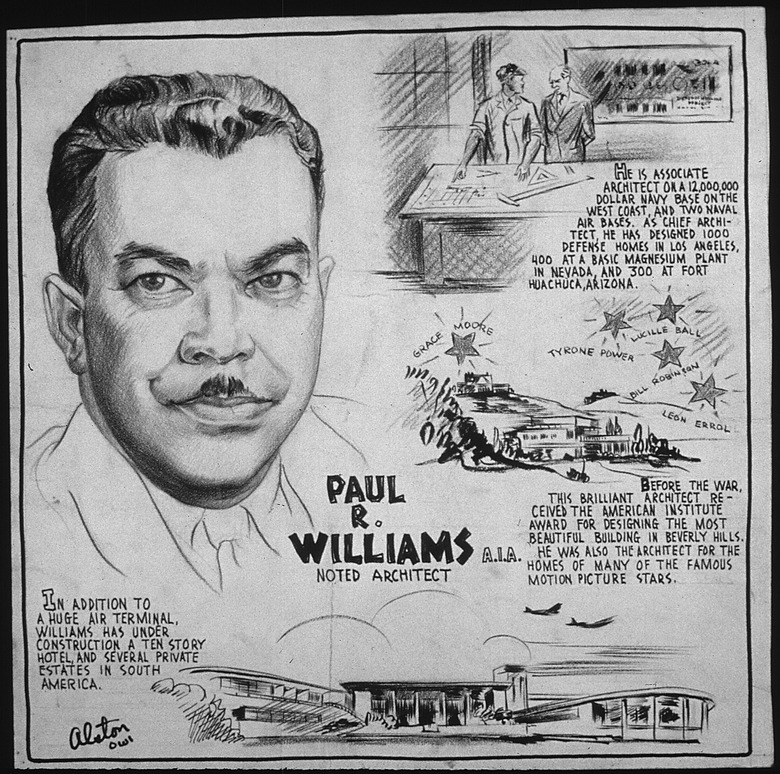

1. Paul R. Williams (1894-1980)

1. Paul R. Williams (1894-1980)

With an extensive clientele of Old Hollywood's biggest celebrities, Paul R. Williams has been dubbed an "Architect to the Stars." Despite being discouraged from entering the field because of the potential racial discrimination and isolation he might (and did) experience, the highly-gifted Williams established an esteemed reputation and became the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1923.

A man of style and grace, he is revered for his versatility and designs that convey messages of glamour. He frequently included elements of traditional revivalism with show-stopping entrances and spiraling staircases. Williams designed homes for clients like Lucille Ball, Frank Sinatra, Tyrone Powers, and J.P Atkins. He is also responsible for the designs of the Second Baptist Church, Saks Fifth Avenue, the Beverly Hills Hotel, and many more. Williams died in 1980. He wasn't given his flowers until 37 years after his death when he was awarded the 2017 AIA's Gold Medal, the organization's highest honor.

2. Amaza Lee Meredith (1895-1984)

2. Amaza Lee Meredith (1895-1984)

Although she held no formal training or credentials in architecture, Amaza Lee Meredith is considered one of the most daring architects of her time. According to the Virginia Heritage Archives, Meredith attended Virginia State University, where she founded the fine arts department. Around 1939, she designed her own home — which would become one of the loudest statements of rebellion against the traditional revival styles valued in Virginia at the time. Azurest South, Meredith's name for the house, is praised for its pioneering and fearless reference to International Style, with its modern characteristics such as a flat roof, geometrically loose shape, minimal and consistent color lines, and smooth exterior finishings. Now, Azurest South is included in the National Register of Historic Places and is Virginia State University's official alumni house.

Meredith was one of very few Black architects during her time. One of her last major projects would be Azurest North, a recreational spot for affluent African-American families in Long Island. She spent her later years modestly building homes for her loved ones.

3. Norma Sklarek (1926-2012)

3. Norma Sklarek (1926-2012)

In 2019, it was reported that more than 80 million people traveled to and from LAX in one year. The millions that departed from Terminal 1 probably have no idea that a Black woman named Norma Sklarek designed that very space. The first African American woman in many categories (licensed architect in California and New York, and AIA member), Sklarek is rightfully praised for her advanced skills in technical details and project management for major buildings.

Her resume is extensive, having worked for many prominent architect firms in high positions, including Skidmore Owings & Merrill, Gruen Associates as director, and Welton Becket & Associates as vice president. At Gruen, her partnership with the renowned architect César Pelli resulted in famous structures like the San Bernardino City Hall, Pacific Design Center, and the U.S Embassy in Tokyo. Her work expanded to include Terminal 1 for LAX, the Mall of America, and many other institutional buildings. In these projects, Sklarek dealt more with production than designing; she once said that architecture "should be functional and pleasant, not just in the image of the architect's ego." Sklarek also helped start the biggest architect firm solely owned by women in the U.S., Siegel Sklarek Diamond. In 1980, she became AIA's first Black woman to be inducted as a Fellow for her continuous positive impact.

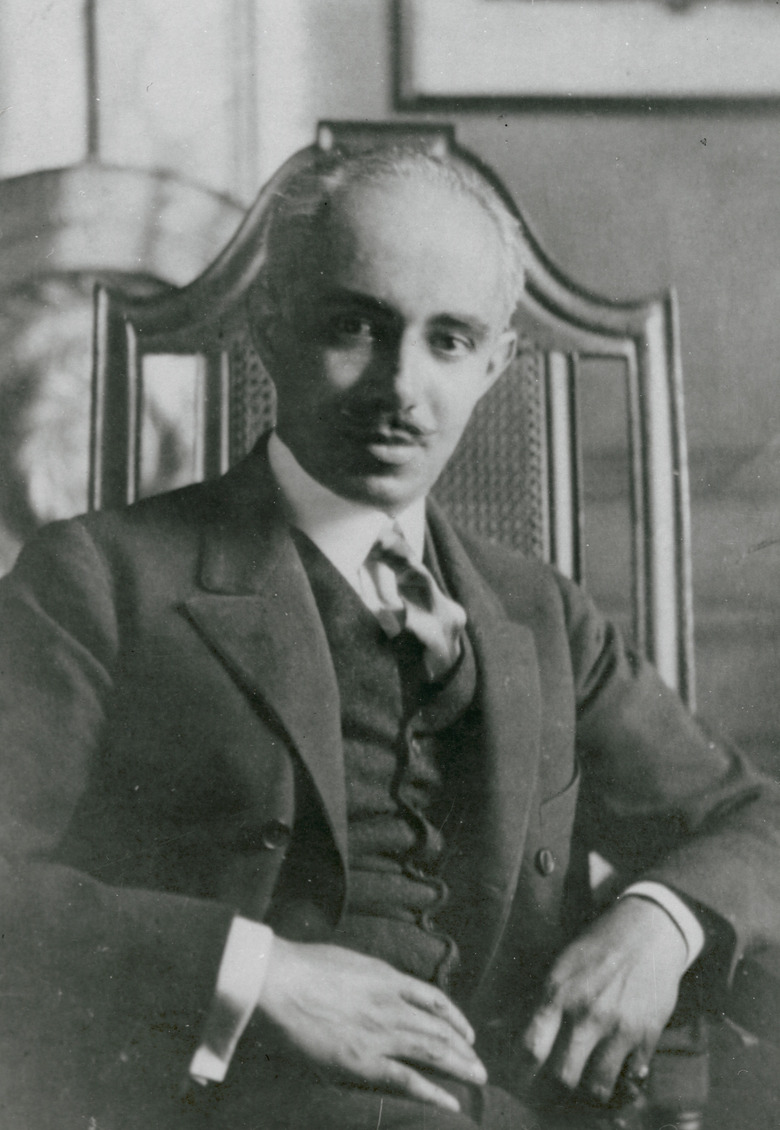

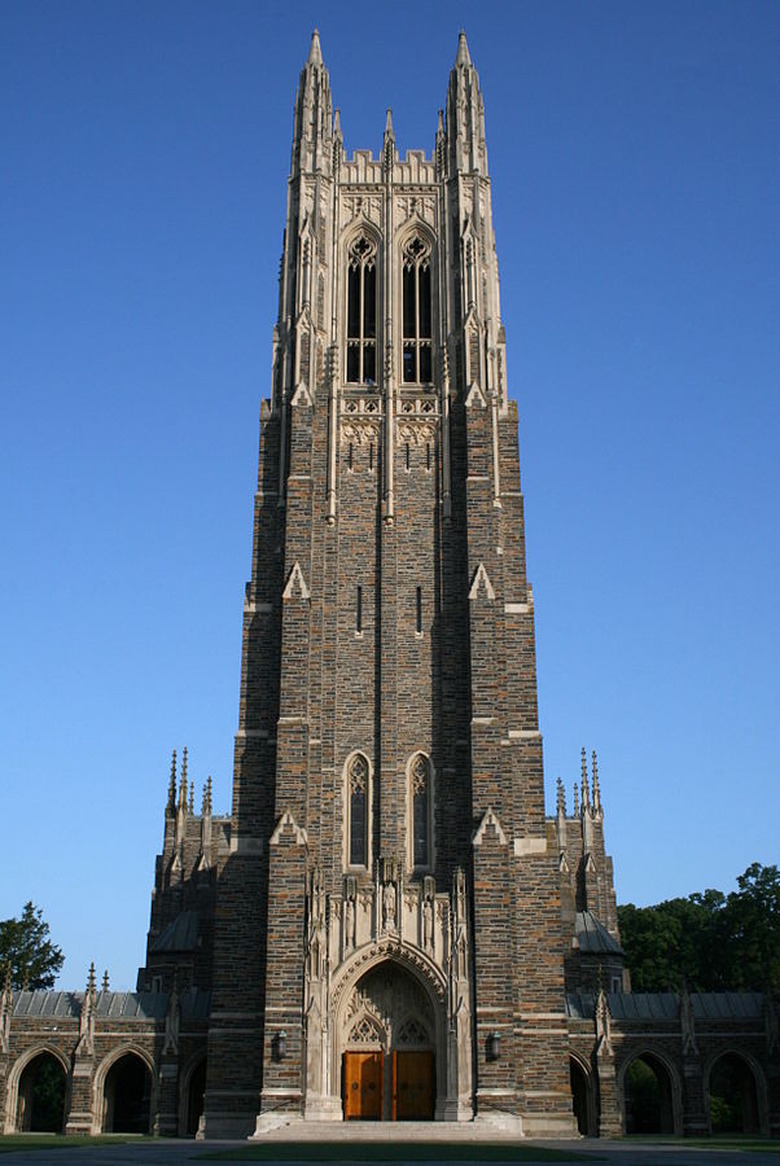

4. Julian Abele (1881-1950)

4. Julian Abele (1881-1950)

Julian Abele is honored for his exquisite beaux-arts style mansions, public buildings, and university campus projects. Popular during the Gilded Age, Gothic and Georgian techniques were his area of expertise. But his real talent was artistically innovating past them to create breathtaking buildings that remained timeless. During his career, he remained loyal to his friend Horace Trumbauer and worked as the chief designer of Trumbauer's firm. He produced works such as the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Widener Library at Harvard University, and the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Abele's most famous and highly-praised work to this day is his brilliant unification of Duke University's west and east quadrants with the creative intermingling of traditional English revival designs, designed in the '40s. This accomplishment isn't just trailblazing for its architectural artistry, but for Abele's ability to transcend racial oppression, designing parts of a whites-only campus at a time he wouldn't even be accepted. Four decades would pass before Abele would be publicly celebrated for his work by the University, due to a great relative (who attended the University at the time) who wrote a moving letter that forced the unsung hero back into visibility. In recent years, the west quad has been renamed Abele Quad to honor his tremendous contribution and legacy.

5. Beverly Loraine Greene (1915-1957)

5.

Beverly Loraine Greene (1915-1957)

Beverly Loraine Greene was born in Chicago, earning a degree in architecture from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in 1936 — reportedly the first African American woman to do so. After graduating, she briefly worked for the the Chicago Housing Authority. However, the city's racial boundaries proved too strong and she had difficulty gaining recognition as a Black, female architect.

Greene moved to New York, where she forged strong relationships with prominent firms and high profile public figures. Her works included the Stuyvesant Housing Projects and designing healthcare facilities at the Isadore Rosenfield firm. Her biggest project was in partnership with Marcel Breuer on the UNESCO United Nations headquarters in Paris. Sadly, she passed away in 1957, before much of it was finished. She was remembered as a pioneer and inspiration for younger architects as she remained unwavering in her architectural pursuits despite strong winds of racism and sexism.

6. Georgia Louise Harris Brown (1918-1999)

6. Georgia Louise Harris Brown (1918-1999)

Georgia Louise Harris Brown — by all means a well-rounded architect — rose to prominence for her advanced industrial skills and use of technology. Brown's skills were cultivated by her attendance at the School of Engineering and Architecture at the University of Kansas and the Illinois institute of Technology (IIT), where she learned from Mies van der Rohe. Her former teacher would invite her to work on his Promontory Apartments and Lake Shore Drive Apartments.

In 1953, Brown left the United States and built a lucrative career for herself in Brazil. She worked on projects like the National City Bank Building and the Kodak factory in São Paulo. Her status as an American immigrant allowed her to become the perfect liaison between American companies that desired to build in Latin America and her associated firms. After becoming sick in 1993, she returned to her American home. Nevertheless, she established a strong legacy as a pragmatic designer and left behind a slew of architectural structures, including private homes, factories, and even furniture.

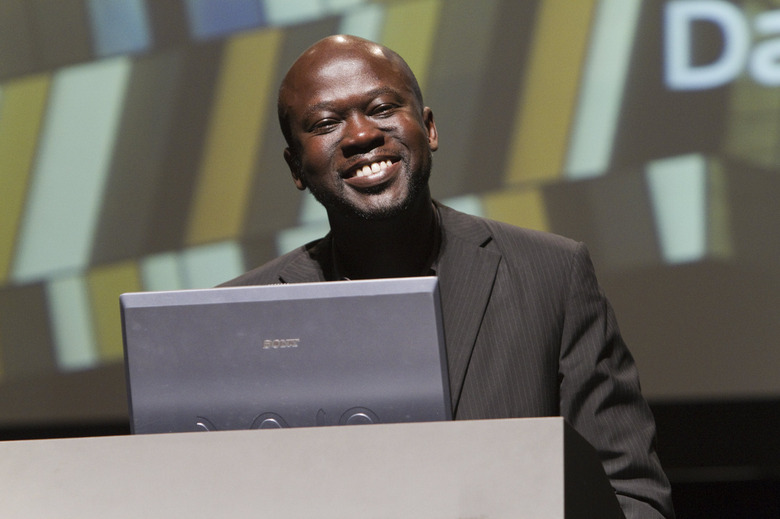

7. David Adjaye

7. David Adjaye

David Adjaye may be the youngest and only living architect on this list, but his groundbreaking work has already secured him a title as one of today's architectural pioneers. Adjaye is a Ghanian-British architect whose work spans across the globe. Having spent a large amount of his life traveling to various countries, he developed a global mindset and empathy for cultures and communities. Thus, social awareness shines through his work, as well as a genuine appreciation of various cultural-specific art forms. The National Museum of African American History and Culture, a $540 million project that Adjaye collaborated on, is inspired by Yoruba tribal art and the "intricate ironwork crafted by enslaved African Americans," according to the museum's site. The museum is intentionally designed to reference Black culture from the inside out, down to the details of functionality and interior design.

Adjaye's eclectic and progressive practice has earned him the Panerai London Design Medal and the title of 2013 Architecture Innovator of the Year by the Wall Street Journal Magazine. Sought out internationally, Adjaye's projects include the Idea Store in London, the Studio Museum in New York, and the Moscow School of Management in Skolkovo. More recently, Adjaye received knighthood from Queen Elizabeth herself. In his remarks, he stated, "I see this not as a personal celebration, but as a celebration of the vast potential — and responsibility — for architecture to effect positive social change."