Elsie De Wolfe Was One Of The First Professional Female Interior Designers

"I know of nothing more significant than the awakening of men and women throughout our country to the desire to improve their houses. Call it what you will — awakening, development, American Renaissance — it is a most startling and promising condition of affairs," announced interior designer Elsie de Wolfe at the beginning of her 1913 book, The House in Good Taste.

Indeed, de Wolfe was known for her good taste not only in houses, but also in the spaces she designed for some of the most elite private clubs, prominent businesses, notable educational facilities, and lavish mansions of the early 20th century — a time when the role of an interior designer, especially for women, was novel. Historically, interiors — particularly public spaces — were executed only by male architects or antique dealers. But with her penchant for delicate French design and pastel colors at a time when dark interiors were all the rage, de Wolfe's aesthetic quickly became noticed.

Born Ella Anderson de Wolfe, she grew up in an upper middle class family and recounts early memories of a life of discerning aesthetics, both about herself (she self-described as a "rebel in an ugly world") and the world around her. When her mother redecorated the drawing room in a then-fashionable dark green William Morris Hunt-style wallpaper, she burst into a veritable tantrum, crying out: "It's so ugly! It's so ugly," as she recounted in her 1935 memoir, After All.

But despite these early inklings of an eye for design, de Wolfe initially followed another creative pursuit: acting. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, she appeared in a series of light comedies, but was noticed more for the elegant ensembles she ordered from Parisian couturiers than for her acting and singing.

Although her acting career did not bring her much commercial success, it did connect her with one of the most important figures in her personal and professional life: Elisabeth Marbury. Bessie, as she was known, was a pioneering literary press agent from a distinguished New York family and represented the likes of Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw, and other celebrated playwrights and writers of the time. She was one of New York's most active society women and was able to step outside of the pre-prescribed role for women in the Victorian era. By the late 1880s, de Wolfe and Marbury had settled into a "Boston marriage," living together as a couple in a storied townhouse near Union Square in New York City.

By the turn of the century, however, it became clear that de Wolfe's acting career was plateauing, and she instead turned to decorating as a way to employ her creative talents. Her early work in set design proved her ability to understand three-dimensional space, and friends encouraged her to pursue decorating. This lead to her first project: the interior decoration and restoration of France's Villa Trianon in 1903. Marbury and de Wolfe purchased the 17th century mansion in Versailles, and together with their friend and socialite Anne Tracy Morgan (daughter of J.P. Morgan), they often hosted high society guests.

For the interior, de Wolfe predominantly used white with pops of blue paint, simple curtains to let in light and air, and floral patterns in chintz for bedrooms. The home highlighted her love for French design, delicate molding and detailing, and lively color combinations such as white and green, which she selected for the trellised pavilion leading out to the garden and pool.

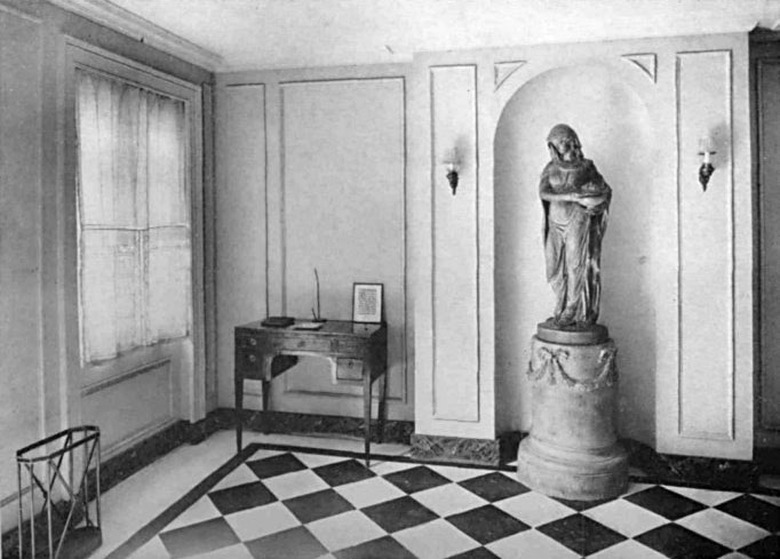

Although the two continued to return to Villa Trianon each summer, they made New York their primary residence. De Wolfe set about redecorating the home she shared with Marbury, employing her characteristic pale wall colors, trellised rooms that brought the outdoors in, and dainty 18th century French furniture. Together, the effect was a much lighter touch than the heavy, masculine interiors of the era. Significantly, however, de Wolfe also rooted her design decisions in the practical, insisting on features like "the little table," or nightstand, which "must hold a good reading light, well-shaded, for who doesn't like to read in bed?" She also believed that furniture should be well-suited for accommodating basics like a clock or telephone.

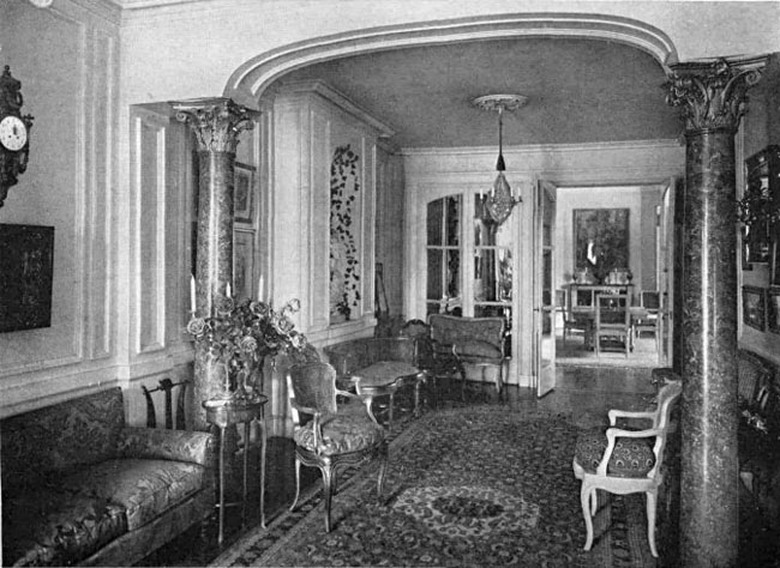

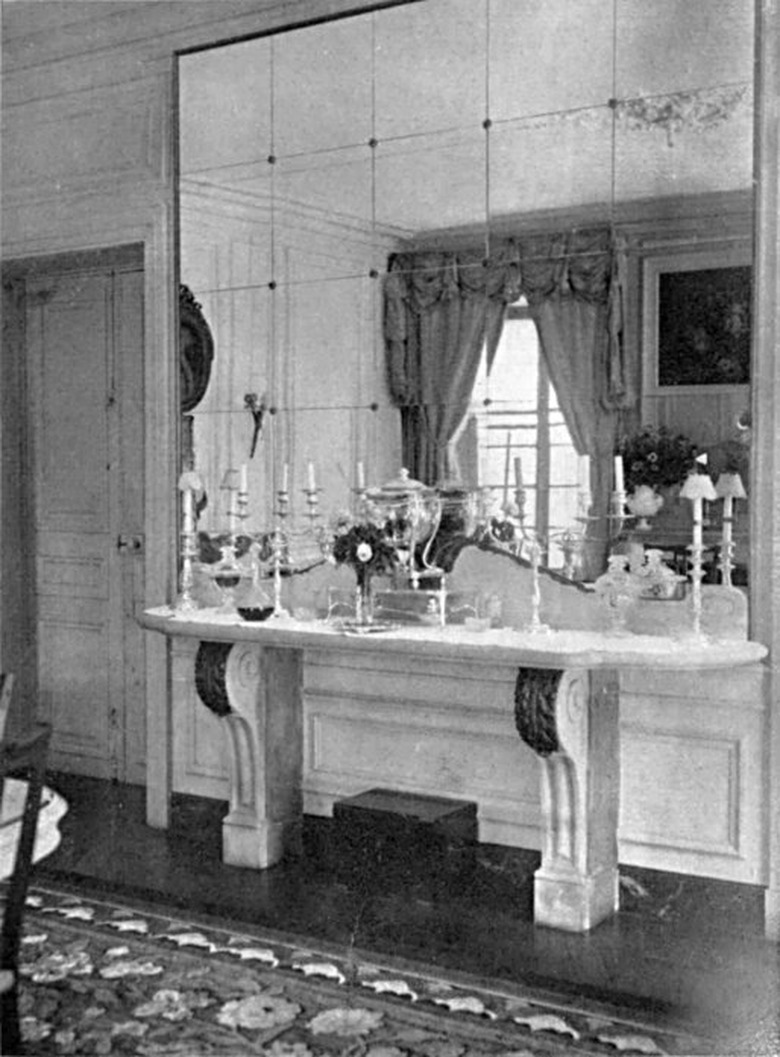

It was through her connections to Marbury and Morgan that de Wolfe was commissioned for the project that would put her name on the map: the interior decoration of The Colony Club in New York, the city's most elite clubhouse for women. De Wolfe was asked by famed architect Stanford White, of the renowned firm McKim, Mead & White, to take charge of the interiors. As masters of the Beaux Arts style, McKim, Mead and White designed some of the most prominent buildings in the United States, including New York's Penn Station, Columbia University's uptown campus, and the second Madison Square Garden. Contracting Elsie de Wolfe cemented her name in the design world, and she approached The Colony Club with vigor, outfitting its rooms with wicker chairs and settees, pastel colors, tiled floors, mirrored walls that bounced light, and an overall air of freshness and femininity. The project was deemed a success, and de Wolfe soon became one of the nation's first interior decorators.

The Colony Club commission, along with her connections within the city's upper class, set de Wolfe up for subsequent projects and opportunities. She collaborated with noted architect Ogden Codman on an Upper East Side townhouse, and in 1911 was approached by the editor of The Delineator to write a column, doling out advice to the magazine's middle-class readers and claiming the home as a place for self-expression, curation, and creativity instead of an ad hoc assemblage of objects. Two years later, the columns were combined to create her bestselling book, The House in Good Taste.

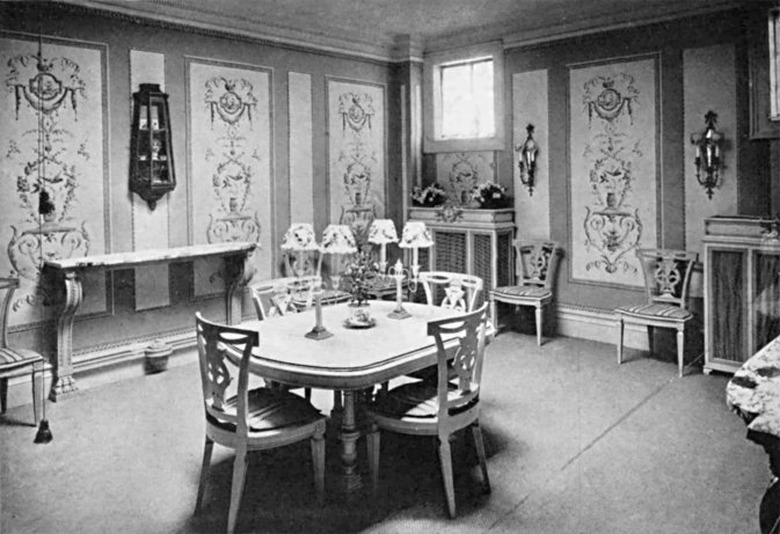

A year later, de Wolfe obtained the commission of a lifetime: the interior design of several rooms in coal and steel magnate Henry Clay Frick's new Fifth Avenue mansion on the Upper East Side. De Wolfe contrasted the darker, wood-paneled spaces of Mr. Frick's personal office and bedroom (outfitted by London decorator and architect Charles Allom) with rooms designated for Mr. Frick's wife and daughter, which were treated with de Wolfe's signature dainty paneling and plaster crown moldings; pale wall colors and drapery; furniture with slim, feminine forms; and fabrics sourced directly from France.

In the ensuing years, de Wolfe continued to establish herself as the go-to interior decorator for the elite, completing a number of social clubs, private homes, opera boxes, and even a dormitory at Barnard College. In 1926, at the age of 60, The New York Times declared her "one of the most widely known women in New York social life" when she unexpectedly married Sir Charles Mendl, a British diplomat.

Lady Mendl, as she became known, continued her thriving interior design business, employing her discerning eye for a select clientele including composer and songwriter Cole Porter and media company Condé Nast. Her spaces became more eclectic yet personable, mixing animal prints with hand-painted Chinese wallpaper; black and white with her beloved beige; and French furniture with English Regency and Chippendale pieces. She also began spending more time in France, keeping a separate apartment from her husband but appearing in countless society functions together, many hosted by de Wolfe herself. In fact, by 1935, she was recognized in Parisian circles as the "best-known American hostess in Europe," per the local Parisian press (which she brazenly repeated in After All).

The outbreak of World War II brought her back to the United States, this time to the West Coast, where she remained until 1946. De Wolfe passed away in France in 1950 at the age of 90, leaving behind Louis XVI furniture, mirrors galore, and unusual pastel pairings like light green and mauve. But perhaps most significantly, she left behind a legacy as a complex (if not even rebellious) figure within high society — a purveyor of good taste and trends, and the harbinger of interior decorating of public and private spaces as a viable field and career. Her legacy emanates from her first book, The House in Good Taste: "Probably when another woman would be dreaming of love affairs, I dream of the delightful houses I have lived in."

Behind de Wolfe's seemingly lighthearted approach to aesthetics lies an undeniably significant place in women's history, design, and women-centered spaces.