Why You Should Know About Studio Loja Saarinen's History

In thinking about design, architecture, and interiors every day, we are always eager to learn more about the historical figures whose influences can still be seen today. Loja Saarinen is one of those people.

You might associate the Saarinen name with her son, Eero, known for his work in the midcentury modern style, with design projects like the Womb Chair and architectural undertakings like the Trans World Flight Center at JFK airport. Loja was married to architect Eliel, known for projects like the Helsinki Central Railway Station. Their daughter, Pipsan, was a furniture, fashion, textile, and interior designer. Loja was an integral part of pooling all their skills together into one significant project: the Cranbrook Educational Community in Michigan.

George Gough Booth and his wife Ellen, known for their work in the newspaper industry, were the ones behind the six institutions that made up the entirety of Cranbrook, which included two separate schools (one for girls and another for boys) and the Cranbrook Academy of Art. Eliel became chief architect of the entire Cranbrook campus, as well as president of the Academy — but Loja made her mark as well.

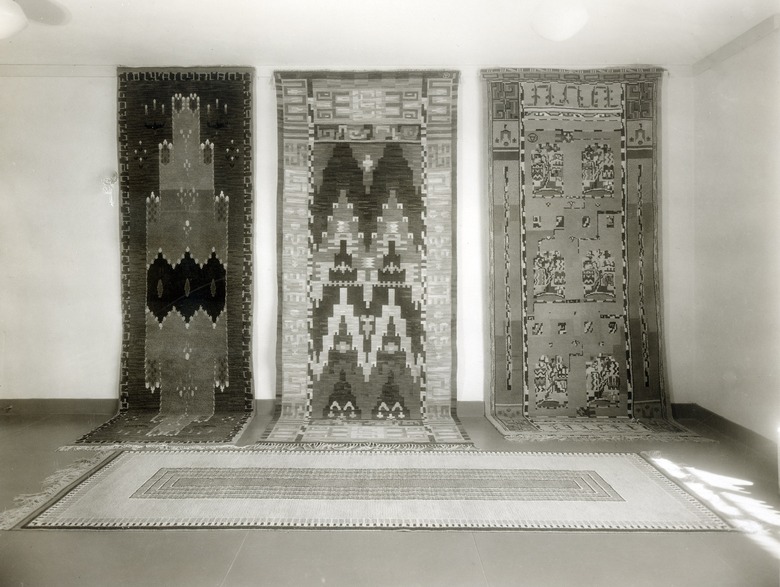

She became the head of the Department of Weaving and Textile Design and also ran Studio Loja Saarinen. Loja established the studio as a commercial venture in 1928 — just a year after the first institution, the Cranbrook School for Boys, was built — and her team produced rugs, window hangings, and more.

"What I think is so remarkable is that a woman who had a background in sculpture and in gardening was able to immigrate to America alongside an already-established celebrity, Eliel Saarinen," Kevin Adkisson, Associate Curator at Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research, tells Hunker. "But then on top of that to say ... 'I will establish this firm to create extraordinarily beautiful, luxurious and custom objects for both use at Cranbrook and for clients around the country ... I have so much more to give, and our family has so much more to give.'"

The studio, at its height, housed 35 looms. To create larger-scale pieces, sometimes four or five weavers would sit at a 12-foot loom. The pieces decorated Cranbrook's interiors but also spaces like the Edgar Kaufman Office in Pittsburgh by Frank Lloyd Wright. One rug was displayed in the Chrysler Company showroom in Detroit; a couple of Fifth Avenue retailers also carried rugs.

Loja was included or had solo exhibitions everywhere from Toledo to Kentucky to Boston. Today, you can find a textile sample and purse attributed to Saarinen in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection.

Booth originally proposed that Loja design rugs and have them woven in Finland, but Loja suggested, instead, that they set up a studio and bring the talent to Cranbrook. That's how weavers like Maja Andersson Wirde and Lilian Holm arrived on the campus.

The exhibition "Scandinavian Design and the United States, 1890–1980," co-organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the Milwaukee Art Museum, is the first to look at "the extensive design exchanges between the United States and the Nordic countries" in the 20th century, according to its exhibition page.

Cranbrook's Kingswood School for Girls, as curator Bobbye Tigerman explains in the exhibition's catalog, was "conceived by Finnish immigrants" and "employed Finnish and Swedish immigrant labor." It's worth noting that some of the weavers, like Holm, also taught classes there. Saarinen and her team of weavers are an integral part of Cranbrook's history, and U.S. design history as a whole.

"Loja's weaving studio was part of a much larger phenomenon of Nordic designers and craftspeople shaping American design," Tigerman tells Hunker. "The canonical history of American design has largely been a story of Central Europeans who immigrated to the United States in the 1930s (think Gropius, Breuer, Mies, Albers). This narrative has obfuscated the critical role played by immigrant Scandinavian designers starting in the early 20th century."

Loja was the only woman heading a department at Cranbrook. And she saw the studio as a commercial project. She knew the power of marketing and chose to "present the workshop in a more artist atelier form," as Adkisson explains. While some photos show her sitting at the loom, she didn't weave the pieces herself (she did, however, often design them).

"She really places herself and her name as indistinguishable from her product so it's a Loja Saarinen hanging, it's a Loja Saarinen rug," Adkisson says. This is totally in line with modern design names, Adkisson adds, such as American industrial designer Russel Wright and his dinnerware.

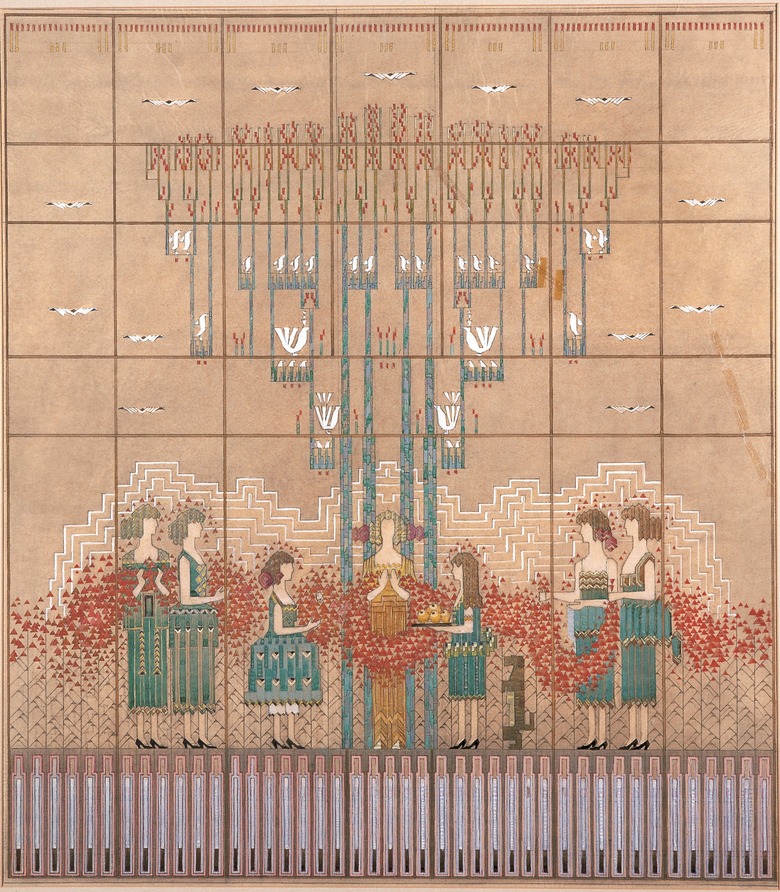

The Studio Loja Saarinen pieces show a strong Arts and Crafts influence as well as signs of globalization — particularly, Adkisson says, stemming from Paris design. Islamic, Native American, Mayan, Aztec, Egyptian, and Japanese motifs were all woven into the fabric of design from this era. The studio used both traditional and modern Swedish techniques.

As new weavers started to join the ranks, the issue of artist credit came up. This was especially true for "The Sermont on the Mount" piece, which Adkisson describes as the last great hanging made by the studio. The younger weavers followed Wirde to the studio but wanted their names to be credited in their pieces — or else they wouldn't create anything anymore. Adkisson points out that the piece the has credit listed as "designed by Eliel and Loja Saarinen, woven by Lilian Holm and Ruth Ingvarsson.

Today, visitors can still visit Cranbrook in person — including the Cranbrook House, Saarinen House, and Frank Lloyd Wright's Smith House. A 1984 New York Times article describes the campus this way: "Cranbrook is like no other institution in the United States. It is part artists' colony, part school, part museum and part design laboratory, and it has never allowed its students to be bound by the narrow lines separating the various design disciplines."

But while Cranbrook would leave a lasting influence — its students include Ray and Charles Eames and Florence Knoll, for example — Loja noticed that her accomplishments were being overlooked. In a letter from 1939, she writes (on stationery that reads "Mrs. Eliel Saarinen") that she "tried to find in vain" any mention of her work in "The Academy News." So she outlined what she'd done from 1938-1939 and signed off with a witty last line: "That's all!"

Studio Loja Saarinen shut down in 1942, but it's an enduring example of the contributions of women to modern design. Tigerman says that many of the women designers in the LACMA exhibition "have not been extensively studied," which points at a larger gap in design history. There's still so much more to the story.