Paul R. Williams' Legacy Is Captured In This Book, Republished By Popular Demand

No matter what city you live in, so much of the architecture around you holds clues to the past. It can be as simple as the style in which a building was constructed. Or perhaps who built it — and the path they took to achieve such a feat.

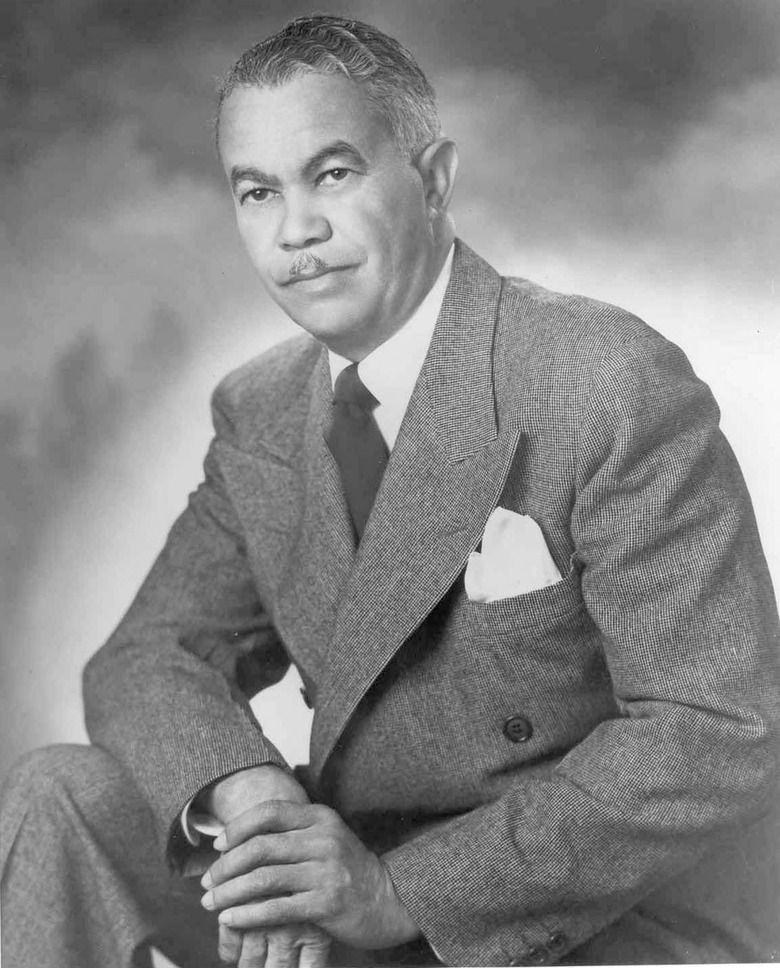

For Paul R. Williams, there were many challenges involved in becoming an architect. A recently updated volume of Paul R. Williams: Classic Hollywood Style on sale November 9 — written by his granddaughter, Karen E. Hudson — sheds light on his career path and the many structures he left behind as his legacy.

While it's a glossy volume with stunning photographs, Paul R. Williams: Classic Hollywood Style is more than just a coffee table book. There's important history within its pages, and a clear through-line that traces Williams' eye for detail, something that Hudson emphasizes in the book's introduction.

Williams was orphaned at a young age and, as Hudson writes, teachers discouraged him from pursuing an architecture career because he was Black. But he didn't let that keep him back, instead spending five decades bringing his designs to life.

These aren't your average homes. They are lavish and carefully crafted, with an attention to how the the outdoors can be incorporate into the indoors. "The California approach still prevails in planning a home," Williams wrote in his notes, which are frequently quoted in the book. "Try to give the guest as he enters the front door a surprise view of a flower garden."

Soon, Williams was known in celebrity circles, designing for Frank Sinatra and Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. His homes have since been associated with even more celebs. According to the Los Angeles Times, in 2013, Debra Messing "sold a home he designed in Bel-Air for $11.4 million in less than a month."

Looking through the book's pages, you start to see some motifs: coffered ceilings, large windows, sweeping staircases, and built-in bookshelves, to name a few. But each structure is different from the last, embracing everything from traditional to Spanish revival to California ranch styles.

"One may be surprised by his multitude of styles, but, to him, his worth as an architect was his ability to listen and to please his clients," Hudson writes.

The book chronicles all these variations through intimate photographs of properties in Ojai, Beverly Hills, Hancock Park, and more. There's a real sense of history to each portrait, illuminating Williams' expertise. Despite their large size, there's a warmth in the spaces. The book lends more insight into each property — from the designing of the fabrics to the homeowners' wishes — that show the complex process of bringing them to life.

It's clear the residents of these spaces respect their history. A 1951 home in Los Angeles remains in the family to this day, according to the book. Another space was remodeled, but not without the owners first consulting with the architect's family.

Williams is part of the history of Black architects' influence on the industry. And it's clear his impact is far-reaching, even into our contemporary times. He was the first Black architect to become an American Institute of Architects (AIA) fellow. He received the American Institute of Architects' highest honor, the AIA Gold Medal, posthumously in 2017. Sadly, he was the first Black architect to receive it, showing how much catching up the discipline still needs to do.

"I came to realize that I was being condemned, not by a lack of ability but by my color," Williams once wrote. "I wanted to vindicate every ability I had. I wanted to acquire new abilities. I wanted to prove that I, as an individual, deserved a place in the world."

In the book's introduction, Hudson highlights that the first home Williams designed — in La Cañada circa 1922 — was significant since land deeds stated Black people couldn't stay overnight in the area. Despite that, Williams was able to make a huge accomplishment.

There's a particular story that's associated with Williams now. In meetings with white clients, he drew his designs upside down, to work around the unspoken social rule that the client wouldn't be comfortable with Williams sitting too close, Hudson writes. In an essay, Williams also referred to this as a means of collaboration, stating, in reference to a client meeting: "It was more than a trick, for, as the room developed before his eyes, I would ask for suggestions and approval of my own ideas. He became a full partner in the birth of that room as I filled in the details of the drawing."

Paul R. Williams: Classic Hollywood Style is a clear reminder of his many contributions to architecture. The Getty Research Institute and USC's School of Architecture recently acquired a host of archival materials from Hudson, giving more possibilities for fruitful research on the architect's career.

Paul R. Williams: Classic Hollywood Style by Karen E. Hudson, $65