Blind Architect Chris Downey On The Need For Multi-Sensory Spaces

To commemorate National Braille Literacy Month, blind writer, performer, and educator M. Leona Godin spoke with Chris Downey to learn more about his journey and perspective as a blind architect.

Chris Downey was an architect for 20 years when he suddenly lost his sight in 2008 after surgery to remove a tumor on his optic nerve. He then threw himself into adapting to life as a blind person, establishing his consulting architectural business Architecture for the Blind, and finding new, non-visual ways of continuing his work as one of few blind architects in the world.

Now, Downey works on projects that range from schools for the blind and ophthalmology clinics to transit hubs and cultural institutions. He also sits on the board of directors for the LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired in San Francisco — an organization that "promotes the independence, equality, and self-reliance of people who are blind or have low vision" — and lectures on architecture and accessibility around the world. This spring, Downey will be teaching a graduate-level studio for the UC Berkeley Department of Architecture regarding Social Justice through Universal Design.

Chris Downey is currently 59 years old and lives in Piedmont, California, which is in the San Francisco Bay Area, but spent his childhood in Nashville, Tennessee. His interest in architecture began when he was just five and his parents hired a modern architect to build their family home, which was constructed in close relationship to its surrounding landscape. Although he was less aware of the house in its design phases, the architect tells Hunker that he "absolutely loved exploring the house while it was under construction — emerging up from the ground — and then loved living and playing in and around the house once it was built."

On his thirteenth birthday, Downey's family moved to Raleigh, North Carolina, and later, he went to North Carolina State University. There, he received his Bachelors of Environmental Design in Architecture and then went on to UC Berkeley for his Masters of Architecture. "I think there are lots of reasons why I was interested in architecture: the creative aspects of it; the way it brings in everything from science to art, sociology, and city planning. You name it, it touches on so many things, but also within that is always the desire to positively contribute to the built environment, to the human experience."

Although his focus has shifted to some extent since losing his sight 14 years ago, Downey's motivations have not wavered: "It's interesting because I think many of the architects that I was most fond of prior to losing my sight have remained so, and perhaps I appreciate them more at this point." He cites Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, Estonian-born American architect Louis Kahn, and the husband and wife team Tod Williams and Billie Tsien out of New York as influences. "What links all of those three together, despite the different styles and approaches, is a profound focus on craft in terms of how things are made, to the point of how it feels to be in the space and to engage [with] the architecture."

These architects are obviously well regarded in terms of the visual aesthetics of their designs, but Downey points to the fact that whenever he visited their work, he'd notice "the really nice custom details of where you would engage with things — the feel of a column as you leaned against it, the craft of a door handle as you entered." Now, without sight, he finds that "those things still resonate, if not more so."

Image description: The LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired reception area with a stairwell in the background. Downey worked as a consultant on this project with Mark Cavagnero Associates Architects. Credit: Jasper Sanidad / 544 Media

Before he lost his sight, Downey worked on a wide variety of projects from public aquariums, theaters, and wineries to academic settings, retail stores, and private residential spaces. Largely because he worked for firms that did not specialize in one particular type of architecture, his projects were "all over the map." "We would do a broad range, cross section of things, and I've always worked that way," Downey says.

Perhaps this ability and interest in working on radically different kinds of projects prepared Downey to be a radically different kind of architect. Of course, certain aspects of his process had to change after blindness. For example, "When it comes down to things like being able to do the drawings, being that I have no sight at all and the computer software relies on sight, there's just absolutely no way for me to interact and drive anything within the digital production of the construction drawings today."

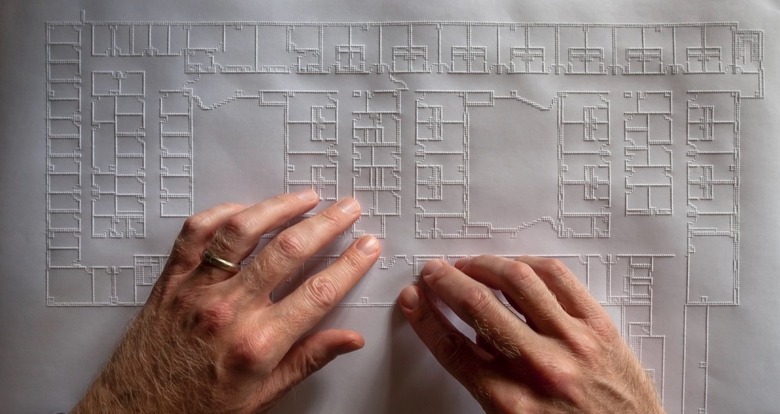

Downey does not only help to create multi-sensory environments, but he also works in new, multi-sensory ways. Although he can no longer interact with inaccessible design software, he still draws. When he collaborates with other architects, they send him PDFs of the designs and he prints them out in relief using large-format embossing printers. Then, using wax sticks (Wikki Stix), he draws right on top of them. Finally, he takes digital photos of those and sends them back in an iterative process that is very similar to what he used to do.

In a situation where many might assume a career change was inevitable, Downey found a way to make his new perspective work for him as well as for others. Instead of giving up architecture, he focused on finding "that place where I have that unique value to offer."

The first chance to prove his value as a blind architect came remarkably fast, when he was introduced to a team that was doing a blind rehabilitation center for the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in Palo Alto, California. He'd been blind for less than a year and his own recent training in mobility and orientation was clear in his mind. This was useful since the client had been asking the architect pointed questions: "How do you know what you're doing? How will your design of this building make any sense for our veterans who are experiencing sight loss and are there for training?"

The architect had to admit that the sighted members on the VA team "could wear blindfolds for a couple hours, but that's not really gonna give the reality of that experience."

It turned out that the VA had design guidelines for virtually every type of building except blind rehab centers. "That's the one that no architect would have any real understanding of because it's so outside of their experience."

Image description: A portrait of architect Chris Downey, who is wearing a blue button-down shirt in front of a dark gray-black background. Credit: Foggstudio

Despite the fact that Downey had only been blind for nine months, he was able to provide them with unique insights. In fact, the very recentness of his own rehab training turned out to be an asset: "Although it wasn't with the Department of Veterans Affairs, it was effectively the same training that their veterans go through. So all that was known to me — it was fresh."

Of course, Downey also had 20 years of prior architectural experience, so he quickly realized, "Here's a whole area of work where I have unique value to offer that virtually nobody else has and, as they say in the business world, it has a high barrier to entry."

Indeed, blindness is not a choice, which can make its sudden arrival feel cataclysmic. Not everyone has Downey's insight that when some doors close as you are abruptly thrown into a new perceptual world, other doors may open. "I was in a unique place, and that really changed how I looked at things. I try not to do the same kind of work, but define those opportunities where I really could offer a unique value, which could give a client or an architect a reason to bring me on for that value."

"Here's a whole area of work where I have unique value to offer that virtually nobody else has and, as they say in the business world, it has a high barrier to entry."

Downey has worked on rehab centers, schools for the blind, ophthalmology centers, and organizations like The National Industries for the Blind, the nation's largest employment resource for people who are blind. More recently, he's realized that he can also bring his unique perspective and talents to public transit because "if you're blind, you don't drive."

However, Downey is not only concerned with the architectural barriers to practical environments such as transit hubs, but also cultural institutions such as museums. "Historically," says Downey, "they've not done a particularly good job of being inclusive." Only recently have museums realized that "the point of being in a museum isn't to go up and down the hallways or through the building. It's actually to access the content."

Thinking about the museum space for patrons with low or no sight can benefit everyone by encouraging conversations about multi-sensory exhibit design. "If you just give people a bunch of eye candy, it's not nearly as effective as making a really compelling, fully immersive, sensory experience."

Image description: The bus deck at the Salesforce Transit Center in downtown San Francisco, which Downey worked on as a consultant with Pelli Clark Pelli Architects. Credit: Jason O'Rear

By the time Downey lost his sight, he wasn't doing a lot of production work himself. "I was really advising and guiding others as they did that work, so they would do the drawings and I might come by their desk, look over their shoulder at the computer, and we would have conversations." Or he might roll tracing paper over the drawing to sketch over it in order to "advance the design, make corrections, and have discussions." Now he's making those sketches using a wax stick on tactile drawings, but "it's effectively the same as a sheet of tracing paper rolled over the base drawing."

In fact, Downey has found that reviewing tactile designs with his fingers has some advantages because it actively puts him in that space. "If I'm in the lobby of the building and I start to go down a hallway or something, I'm mentally in that space and I'm thinking about the proportions, I'm thinking about the material as I'm thinking about the sound, and thinking about light coming through a window or from overhead."

"If you just give people a bunch of eye candy, it's not nearly as effective as making a really compelling, fully immersive, sensory experience."

Of course, it was not as if Downey went blind and could suddenly read tactile drawings. First, he needed to train his sense of touch. "For me, part of the motivation to study Braille was to develop that neurological connection between the touch of my fingertip on a drawing, a tactile drawing, and my brain."

Soon after blindness, Downey's rehab counselor set him up with the embossing printer, and with the help of his technology trainer, he printed out drawings that he knew well from having worked on the project not long before he lost his sight. His trainer had been blind since the age of four and was quick to navigate the drawings, asking questions while Downey himself struggled to make sense of this new medium. "I got the plan out, laid it down on the table, and we both started reading it, and the trainer, who'd never seen an architectural drawing in his life, was all over the place, asking me all sorts of questions: 'What's this? This is cool!'"

Meanwhile, Downey was lost and, naturally, a bit frustrated: "This is my stock-in-trade, and I don't know what's going on!"

He quickly realized that what was going on was that his trainer had decades of taking in information through his fingertips behind him. "It made me realize quickly that ... he's a super efficient Braille reader. He's really developed that connectivity." So Downey started Braille training both for the utility of being able to read, but also to regain access to drawings because "drawings are the currency of the business of architecture."

Image description: Chris Downey touching a tactile drawing in the Architecture for the Blind studio. Credit: Chris Downey

Tactile drawings are critical for Downey to do his work, but they can also make the process accessible and inclusive to his clients. He recalls working on the Independent Living Resource Center in San Francisco, which is not specific to blindness, but deals with all types of disabilities. Their executive director was blind and had been blind since birth. "It was a really wonderful opportunity. The very tools that I use, the drawings that I used in my way of working, the wax stick and everything, made the process accessible to her and gave her agency as the executive director of their organization. She wasn't then relying on people with sight to tell her about the plan and tell her about the design. She loved it when I rolled out drawings. We'd be in a meeting or reviewing the drawings together, and she'd ask her staff, 'What do you think about this stuff?' And they're like, 'We don't know. We can't see the drawing — your hands are all over the place!'"

Downey almost can't help making his blind clients feel more comfortable so that they have "the agency they need to contribute meaningfully to the process." He notes, "For me, it's a natural part. For any other architect, it's like, 'Oh my God, what am I doing here? How do I do this?'"

"For me, part of the motivation to study Braille was to develop that neurological connection between the touch of my fingertip on a drawing, a tactile drawing, and my brain."

This speaks to the need for more blind and low-vision architects. Downey offers his support to students who are interested. "They're all low vision and in schools of architecture around the U.S. — one in Texas, one in Georgia, and one in Massachusetts. I do mentor them to the extent that I can, and I put them in touch with each other, so they have their own support network." There's a fourth student who is blind and looking to transfer from engineering to architecture, as well as an intern established and sponsored through the California Department of Rehabilitation. The intern is currently enrolled at a community college and is hoping to transfer into an architectural program. As of now, it's basically a virtual internship, which is "suboptimal," but "better than nothing."

Though the answers to many practical questions are still being addressed, there is hope that not only the students' education will expand, but also the discipline itself, through a growing emphasis on thinking in non-visual terms. In 2019, Downey co-taught an intensive week-long mini course at the UCL Bartlett School of Architecture in London. "The dean of the school was not only interested to explore the means by which to make the architectural education process accessible to students who are blind or low vision, but he was actually more interested in what they had been missing by virtue of the fact that they had not had students who are blind or low vision in their school."

A space can reveal its aesthetic beauties or flaws not only through the visual, but also by way of tactile and acoustic elements. However, Downey points out that there's often a "knee-jerk" assumption on the part of the sighted that blind people go around feeling everything with their hands. But most blind people do not like feeling public walls any more than your average sighted person does. The Municipal Transit Authority in San Francisco put up tactile maps in every station and were confused as to why people weren't using them. Downey explained, "Well, would you want to go feeling all over the walls in the Transbay Terminal to find if there might be a tactile map someplace, and then feel that map where everybody else had been?" Downey concludes: "That's not realistic or desirable."

Downey focuses on "those areas where you really can anticipate that the tactile experience would be meaningful and predictable." For many blind people, that's not necessarily what's under your hands, but also what's under your feet. "A cane extends your sense of touch from your hand to the tip of your cane as it meets the floor. So you get the haptic feedback through the cane of what the material is." Downey cites the polished floor of the main circulation path of The LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired buildings in San Francisco as an example of underfoot aesthetics: "It is just silky smooth and it has a really nice feel to it through the haptic feedback of the cane. And you can really feel discernible things within it as you move around."

It also brings factors like good acoustical feedback into play. For an attuned blind listener like LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired CEO Bryan Bashin, this offers the means to recognize his staff by the sound of their footsteps. "So he might hear a cane tap at the other end of the space and know who it is." Downey has also noticed not only the identity but the mood of his coworkers in an office space. This can be useful when determining "whether to engage with them at that moment or not!"

Image description: A hand on a wood handrail at the LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired. Credit: Foggstudio

Attention to the non-visual elements of a space do not only benefit people with low or no sight; we all engage with architecture and design on many levels. The way a body meets a counter's sharp edges or curved lines and the way feet strike wood, carpeted, or marble floors gives us constant (conscious or unconscious) feedback. Downey points out that what we might dismiss as details, such as door pulls or handrails, are exactly the points of contact between the individual and the architecture. "You can really think about that not just as utilitarian fixtures or as stock items off the shelf. You can design that to be part of the experience."

Returning to Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, Downey explains: "There's a lot of things that he did to anticipate the presence of the human body in the space."

"You can really think about [details like door pulls or handrails] not just as a utilitarian fixture or as stock items off the shelf. You can design that to be part of the experience."

A moment that stuck with him from an encounter with Aalto's care for detail was the door handle on one of his churches in Finland. "It was just amazingly crafted, and it had a nice curvature to it that fit the hand well, and then it was wrapped in leather where your hand would actually grab it. So there are so many things to think about."

Encounters like that inspire Downey to translate the sense of beauty and delight he experienced and created as a sighted architect into the tactile experience — "to extend that same sense of care of design and generosity from the visual, and to really share that sense of quality."