Architect Julia Morgan Defied Many Odds

(Victoria Kastner spent more than three decades as Hearst Castle's official historian. Now an independent researcher and sought-after lecturer, she is the author of Julia Morgan: An Intimate Biography of the Trailblazing Architect, a newly published book).

Julia Morgan was a lifelong trailblazer. In 1898, she was the first woman admitted to study architecture at the world-renowned École des Beaux-Arts in Paris (founded in the seventeenth century). Less than four years later, she became the first woman to graduate from its demanding program (which generally took six years to finish, though many never completed it). In 1904, she was the first woman licensed to practice architecture in California.

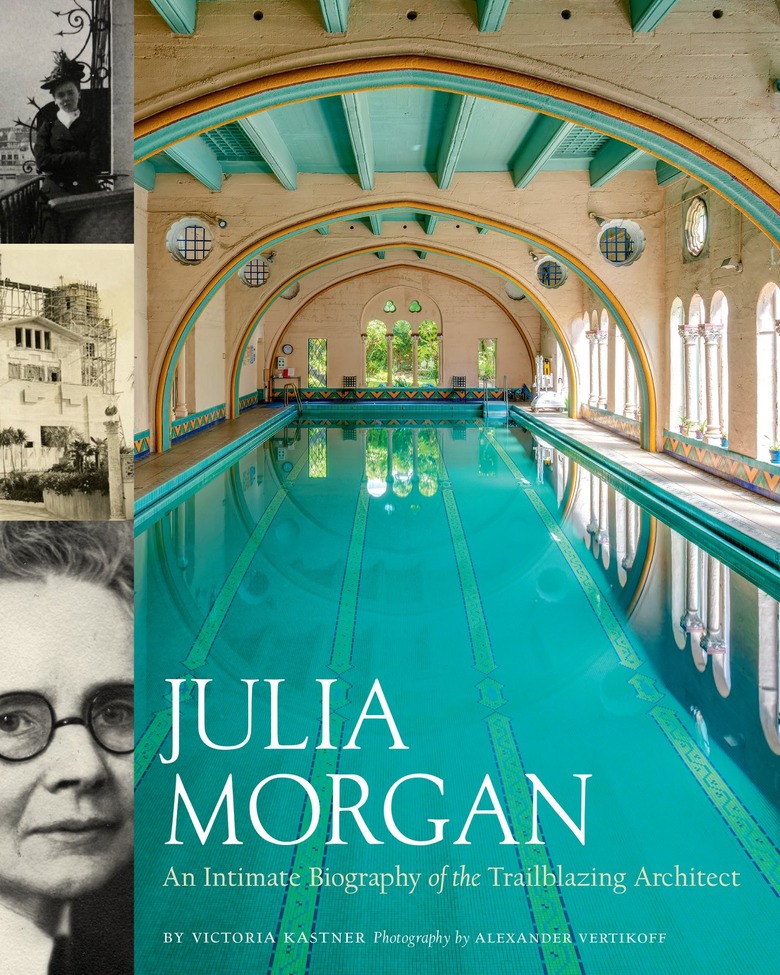

Few other architects could match Julia's output during her 50-year career: an estimated 700 structures, including William Randolph Hearst's two lavish residences — one at San Simeon and one in Northern California — which rank among the nation's largest. San Simeon alone contains approximately 110,000 square feet of enclosed floor space, divided among a half-dozen independent structures.

Yet it receives only one number — Job 503 — in Julia's records. Though the exact quantity of her designs may never be known, due to omissions in the historical record, it is fair to say that Julia ranks among the 20th century's most prolific architects. With so many groundbreaking achievements, therefore, the most recent one could be considered long overdue. In 2014, the American Institute of Architects posthumously awarded Julia its Gold Medal. She was their first female recipient in the prestigious award's 100-year history.

After America joined the war (editor's note: World War I) in April 1917, Julia devoted much of her time to designing YWCA hostess houses in San Diego, San Pedro, and Palo Alto. These homelike buildings, constructed near military training camps, provided visiting families with comfortable accommodations, including sleeping quarters, reception rooms, a cafeteria, a nursery, and occasionally even athletic facilities. The San Francisco Examiner reported: "Miss Julia Morgan . . . has offered to design any or all of the hostess buildings at the camps. This was to be her bit, she said, toward the war work of the YWCA."

In a national effort, Julia collaborated with two women with whom she had studied architecture in Paris: Fay Kellogg, who designed hostess houses in the Southeast, and Katherine Budd, who designed them in the Midwest. Julia was also put in charge of overseeing all YWCA construction, requiring her to "superintend the plans for hundreds of buildings in this country and overseas. Doubtless her own ideas will be incorporated. . . . as [her buildings] are models of utility, comfort, and good taste."

While the YWCA concentrated primarily on the needs of young women aged 18 through 25, thousands of independent clubs across the country provided similar benefits for adult women. In the nineteenth century, many of these societies focused primarily on self-improvement; by the 1920s their purpose had expanded to include community improvements.

When the California Federation of Women's Clubs was founded in 1900, it represented forty organizations with a combined membership of 6,000; by 1920 it represented 531 organizations with a combined membership of 55,000. Julia designed two women's clubs early in her career — San Francisco's Century Club in 1905 and Los Angeles's Friday Morning Club in 1907 — and several more over the next two decades. She herself attended the founding meeting of the San Francisco Professional Women's Club in 1916 — an organization that promoted networking and potential career advancement.

Two excellent examples of Julia's women's clubs are the Saratoga Foothill Club and the Sausalito Woman's Club, both built between 1914 and 1918 in the First Bay Tradition. On the Saratoga lot, which was located at the base of a hill, Julia stressed horizontality, designing a single large room with an aisle on one side for the kitchen and other services.

Its interior was bathed in light from two walls of windows and an additional rose window, while its redwood-shingled exterior was softened by pergolas that helped it blend into the residential neighborhood.

For Sausalito's hillside site overlooking the bay, Julia designed what appears to be a simple redwood-shingled rectangle. In fact, the building has eighteen corners, in order to take advantage of its angular lot and dramatic ocean views.

Walter Steilberg was working in Julia's office during this time, when they had what may have been their only disagreement. She sent him to shoot dozens of her buildings for a photo essay that ran in the November 1918 issue of Architect and Engineer of California. Walter surprised her by writing an accompanying article that included these breezy lines:

"Gone are the good old days when domestic architectural design was simply a matter of crowning a hilltop with a picturesque pile that would keep out most of the rain and all of the neighbors." He recalled years later that this phrase "didn't delight Miss Morgan. She thought [it] was so trivial. . . . She was displeased with it. I think her only comment was 'The building should speak for itself.'"

Excerpt from Julia Morgan: An Intimate Biography of the Trailblazing Architect by Victoria Kastner, published by Chronicle Books 2022. Reprinted with permission from Chronicle Books.