Why The All-Gender Bathroom Is Still A Battleground

The bathroom. It's a space so mundane that most people don't think twice about it, nor do they want to — it is where we go to relieve ourselves, after all. Bathroom access only becomes a concern when a public restroom isn't readily available, and for those of us who do not have disabilities (or who don't live in New York City), these moments are few and far between.

But the mundane nature of the bathroom distracts from its complicated history as a politicized place. The way public facilities are designed has always reflected the values and biases of people in power — take, for instance, the race-segregated restrooms and drinking fountains of the 1960s. "As soon as you flush the toilet," noted Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek, "you're in the middle of ideology."

This continues today, although the target has shifted to another marginalized group. For many of the over 1.4 million transgender people living in the United States, bathroom access is a daily concern. Right-wing lawmakers in numerous states across the country have wielded their policy-making power to limit trans people's access to bathrooms that align with their gender identity. This tide of so-called "bathroom bills" has hardly receded in the aftermath of President Donald Trump's administration. 2021 actually saw a record-high number of anti-trans bills brought forward in state legislatures, with more — like a bathroom bill that passed in Alabama's legislature last month — poised to follow suit.

As LGBTQ+ advocates work to combat these bills, architects and lawyers seek to tackle the issue of bathroom access at its source. The history of bathroom design is littered with examples of exclusion and prejudice, yes, but its future may very well be more inclusive than ever.

A Shitty History

A Shitty History

Gender-neutral or -inclusive bathrooms might seem like a new-fangled invention, but the opposite is true. For the majority of human history, including antiquity and the Middle Ages, public facilities were separated along a more objective binary: bathing versus, well, everything else one does in the bathroom. People of all genders washed together at mixed-sex bathhouses. This was long before the advent of modern waste-management systems, so everyone was intimately familiar with their own excrement. You could call shit the great equalizer, with one's social status, not sex or gender, determining whether they took bathroom breaks at co-ed communal latrines or the city streets.

Early American history paints a similarly low-tech picture. Municipal waterworks systems weren't implemented in most major cities until the mid-19th century. Before then, you could scarcely find a toilet located inside an actual building, much less multiple indoor toilets separated by sex. It's a phenomenon legal expert Terry Kogan, professor emeritus at the University of Utah S.J. Quinney College of Law, has studied at length. "Until the 1840s, America was a really disgusting place," he tells Hunker with a laugh. "People would basically dump their refuse out of their windows into sewers across the street. And the outhouse, the privy, was also the way that most people except for the very rich relieved themselves."

"The idea that there was a 'men's privy' and a 'women's privy,' one outhouse with the moon and one with the sun, is an absolute myth." — Terry Kogan

Sex-segregated indoor bathrooms with toilets — or water closets, as they are occasionally referred to in architecture and construction — actually emerged as a byproduct of the Industrial Revolution. Women were entering the workforce, and thus the public sphere, in record numbers, but problematic Victorian-era ideologies around women's innate weakness and vulnerability were still pervasive.

"Architects in the early 19th century needed to find a way to build structures — buildings, forms of transportation — that on one hand would accommodate women and their strong support for economic development, but on the other hand would somehow tip its hat to this strongly held 'separate spheres ideology,'" Kogan states. "Once the practice began of separating men's restrooms from women's restrooms, it became sort of understood that that was the proper way to configure architectural spaces in public buildings."

This "tacit code" was eventually reinforced through laws requiring separate bathrooms for women, which popped up in different states across the U.S. between the 1880s and 1920s. It then bled into 20th-century building and plumbing codes, some of which are still in place today. Interestingly enough, women-only parlor rooms and waiting rooms were also common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Sex-segregated bathrooms, it seems, are a lone holdover.

If history proves one thing, it's that outdated cultural values, not some biological or technological imperative, set this precedent. This is the core thesis of Kogan's writing for Stalled!, a multidisciplinary research project addressing the issue of trans folks' access to "safe, sustainable, and inclusive public restrooms." He co-founded the initiative in 2015 alongside Joel Sanders, principal architect at JSA / MIXDesign and professor in-practice and director of post-professional studies at the Yale School of Architecture, and Susan Stryker, professor emerita of gender and women's studies at the University of Arizona.

Stalled! originated in response to the high-profile lawsuit involving Virginia high schooler Gavin Grimm, a young trans man who sued his school district after administrators implemented a new policy limiting girls' and boys' bathroom access to students of the "corresponding biological gender." At the time, the topic of bathroom access for trans people was new to mainstream audiences, but moral panic around bathrooms was as American as a Fourth of July barbecue. "Pretty much every decade," Stryker told 99 Percent Invisible, "there's been some controversy about public toilets."

The one constant? Bathroom design itself, which hasn't changed all that much since the late 19th century. Given the sexist beliefs that birthed these design standards, it is no coincidence that contemporary bathroom-bill proponents portray trans women and girls using women's facilities as "endangering" cisgender women, even in the face of empirical data that suggests otherwise.

The Future Is Now

The Future Is Now

Sex-segregated, multi-user public bathrooms are still widespread throughout the U.S. and Europe, but why should centuries-old ideals dictate how contemporary architects approach spatial design? A.L. Hu, a New York City-based licensed architect and design initiatives manager at Ascendant Neighborhood Development, grapples with this issue both professionally and personally. Hu is nonbinary, so sex-segregated bathrooms force them to make some "pretty uncomfortable" decisions for their personal safety.

"Where will I not get harassed?" they tell Hunker. "Will people yell at me for being in the women's bathroom because I have short hair? I've definitely gotten responses of like, 'Whoa, are you in the right bathroom?'"

By definition, sex-separated bathrooms invalidate Hu's identity as someone who does not ascribe to the gender binary. Even gender non-conforming cisgender people, such as butch lesbians, report encountering harassment in gendered restrooms.

Hu's experience mirrors data from a 2019 Harvard University study, which found that trans and nonbinary students faced higher incidences of harassment and sexual assault in school districts with anti-trans bathroom policies. Researchers weren't able to pinpoint what exactly caused this increased likelihood of assault, but they did note that such policies "seem to be a marker for an environment where trans and nonbinary youth are at risk."

Hu came out as queer and nonbinary while completing their graduate studies in architecture at Columbia University in 2015, the same year that Stalled! was created. A lot has changed since then, including the language architects and advocates use to describe inclusive facilities. "I've definitely heard 'gender-neutral,' and I tend to correct people to use 'gender-inclusive,'" they explain. "Gender is never neutral. Even if you are trying to design something that's 'gender-neutral' or 'agender,' you're still being political about it because you're making choices."

"It's not like we can blot gender away and be totally neutral about anything. In the end, that design choice is still going to be a political one." — A.L. Hu

Kogan and the rest of the Stalled! team advocate for a series of gender-inclusive design choices grouped under two overarching categories: single-user and multi-user bathrooms. According to Stalled!'s website, the former "maintains the status quo with a single-occupancy room, not so different from the single-occupancy bathrooms mandated by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)."

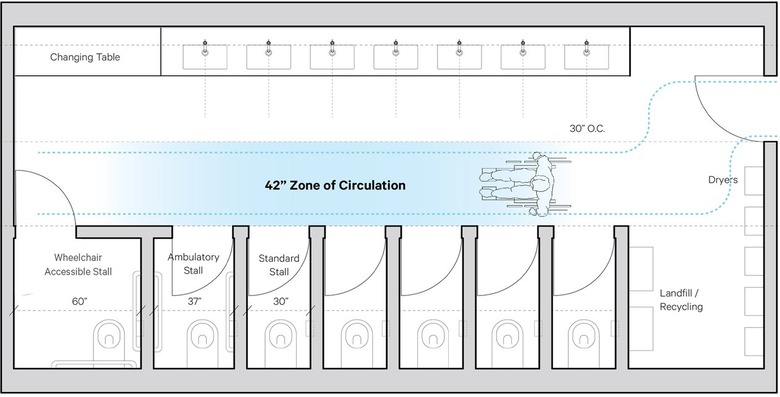

The team's gold standard, however, is the latter. Budget permitting, this gender-inclusive, multi-unit model nixes urinals and incorporates "stalls with floor-to-ceiling doors," which eliminate the visual gaps many of us have come to associate with American-style public restrooms. It's a standard Hu emphatically agrees with: "Why do these [gaps] even exist? We have dressing rooms that are more private than bathroom stalls!"

This model also accounts for people who use wheelchairs and parents of infants who need access to changing tables. "Accessibility goes beyond where a wheelchair fits," Hu adds. "Are there changing tables in every public restroom regardless of what gender it is? Are there sinks that are low enough?"

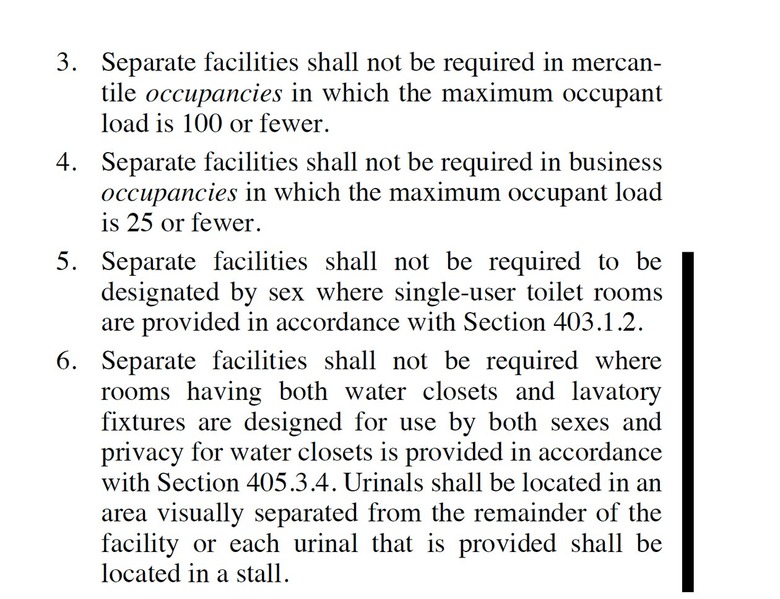

Up until just a few years ago, Stalled!'s gold-standard model wasn't permissible under the International Plumbing Code (IPC), a set of regulations for spatial design with regards to plumbing. Although building and plumbing codes are "designed by architects so architects can make buildings better" — and they often do fulfill that intended purpose, especially with regards to personal comfort — Hu says that they inadvertently reflect existing paradigms of oppression. (The U.S. also has its own tiers of state and local building and plumbing codes, although most states in the U.S. currently operate under IPC standards.)

The IPC's regulatory body, the International Code Council (ICC), formed in 1994. It only amended the IPC to permit the construction of all-gender, multi-user public restrooms in 2019. And that amendment was the direct result of campaigning from Kogan, who testified at a 2018 ICC hearing on behalf of Stalled! and the Transgender Law Center. In other words, that modification did not come about due to a sudden change of heart.

The newly amended version of the IPC was released in 2021; now, advocates like Kogan are in a "two or three year" holding pattern as states and municipalities decide whether to adopt it. Local officials also have the power to pick and choose which provisions are implemented, meaning they could opt out of this amendment altogether.

In the meantime, there are plenty of code-permissible steps that architects, building owners, and business owners can take to make their public facilities more gender-inclusive. There's always the option of erecting single-user bathrooms for patrons of all genders, which the IPC has allowed since 2018.

A lower-lift tweak could even be as simple as altering the signage on an existing single-user bathroom.

"When you can't redo everything just yet, and you still have one restroom with urinals and stalls and one with stalls, you put a sign on the door that says, 'This one is urinals and stalls,' and 'This one is just stalls,'" Hu says. "Something as simple as a toilet on the sign and moving away from having those binary-specific signs ... is super important."