Karen Braitmayer On The Future Of Accessible Architecture In The U.S.

If anyone can speak to the state of accessible design, it's Karen Braitmayer.

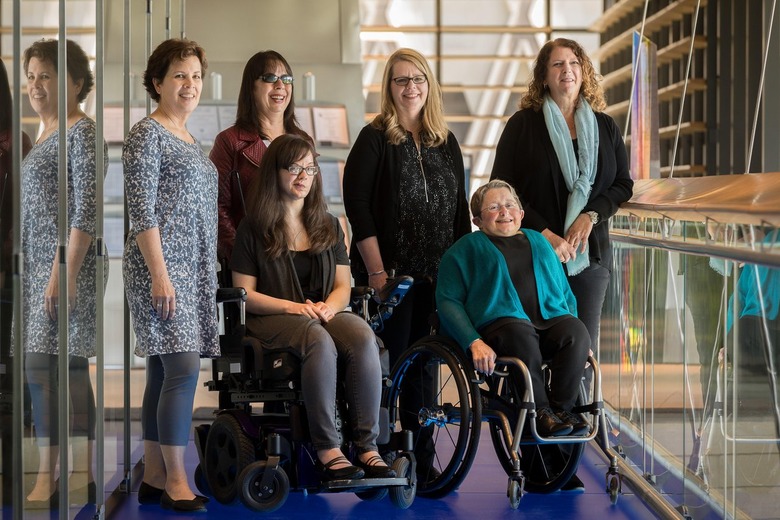

A licensed architect, American Institute of Architects (AIA) fellow, and founder of Seattle's Studio Pacifica consulting firm, Braitmayer has been making residential and commercial buildings more inclusive of folks with disabilities for over 25 years. She is a lifelong wheelchair user herself, which brings invaluable perspective and sensitivity to her work. Her emphasis on promoting "barrier-free design" without sacrificing aesthetic appeal attracted the attention of former President Barack Obama, who appointed her to the United States Access Board in 2013. She still serves on the board today.

In honor of Disability Pride Month, Hunker caught up with Braitmayer via video call to chat about the lack of architects with disabilities in her field, the pros and cons of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and what the future of accessible design will look like.

Hunker: What inspired you to get into the world of accessible design?

KB: I started my architecture career thinking that I was just going to be a generalist architect. [But] I started finding that in my work, I would look over the shoulders of my office mates and see design solutions that I thought were perhaps better ways to do things. 'Why are we putting stairs here? Or, is there another way to enter that building?' My colleagues started asking me for advice and suggestions, and then I thought, 'I probably need to be trained to be sure I'm giving the correct advice.' So I got really interested in accessibility, but it wasn't until 2006 when staffing changed at my personal firm, [Studio Pacifica], that I realized all the work I wanted to do and was [taking on] in the firm was around accessibility.

I moved to accessibility as the focus of my work. I kind of do it selfishly — I want all the buildings I work on to be as accessible as possible for me, my friends and family, and the disabled community. I can't imagine doing anything else now.

Hunker: How does your own disability inform your work?

KB: I have osteogenesis imperfecta. For me, it's largely a mobility-based disability. I'm a lifelong wheelchair user. I'm now using a power chair. It also affects my hearing. Growing up as a chair user, I see the world a little differently than folks who walk. I have been known to walk right by sets of stairs looking for the elevator, totally oblivious, because I'm looking for the feature that's going to support me.

Learning to understand my hearing loss has been a much bigger challenge because communication is key to the way we live. So I'm much more supportive in understanding appropriate acoustics and lighting to enable folks to read lips, or sign if you're fluent in ASL. The way our spaces are designed can make that easier or harder.

Hunker: I love the phrase 'barrier-free design,' which you use on Studio Pacifica's website. Can you describe your design philosophy?

KB: The experience of disability is largely influenced by the experience of your environment. It is, as [inclusive designer] Kat Holmes has said, a mismatch between your physical environment and the experience that you have in your body. Our goal is to eliminate as many of those barriers as possible, thereby enabling people to be able to use all the skills and attributes that they have. Everyone wants to be able to live a full life and participate in community, whether that's going to school or work, raising a family, or engaging in your favorite hobby.

Hunker: What are some of the most common accessibility issues you and your team address?

KB: Making housing accessible is a big challenge, and I would argue there's never enough accessible housing. Here in Washington state, we do have a requirement that 5% of all multi-family housing should be built to be wheelchair-friendly, but 5% is not enough. We'd like to make all housing — even single-family housing — more accessible.

In terms of other issues or barriers, I think about just getting in the door, being able to ensure that there's a smooth, easy path from however you got to that building into the door — even small things like providing power-sliding doors. Those are so welcoming to everybody.

Hunker: Let's talk about the ADA. Broadly speaking, how did this law change the game for accessibility within design?

KB: I think the ADA was, hands down, the most impactful law to influence architecture in relationship to accessibility. It's because of its breadth: It covers not just federal buildings, but state and local governments, and all public accommodations. So right there, that's a huge impact. But even the folks who wrote the most recent version acknowledged that there's definitely more work to be done.

There's additional research needed to ensure that the dimensions and requirements match the needs of people who are using today's technologies. There needs to be more work around the deaf and hard-of-hearing community, as well as the blind and low-vision community. And of course, the neurodiverse community is not even really acknowledged in the language.

Hunker: At Studio Pacifica, you often work with clients who want to "go beyond" whatever accessibility features are required by law. Can you give some examples of that?

KB: I think our clients are interested in trying out new things — looking at increased use of new technology, way-finding, tactile information for folks in the low-vision, blind, and deaf-blind communities. We've also been mining the experience of people with disabilities themselves to ask, "Where are the gaps? Where are the pinch points? What ideas do you have?" People with disabilities actually have been hacking their way through the world for a long time, so we try really hard to listen to the disability community, and then we just pilot things and see if people like it.

Hunker: Have newer chronic illnesses, like Long COVID or post-COVID conditions, come up in your work at all?

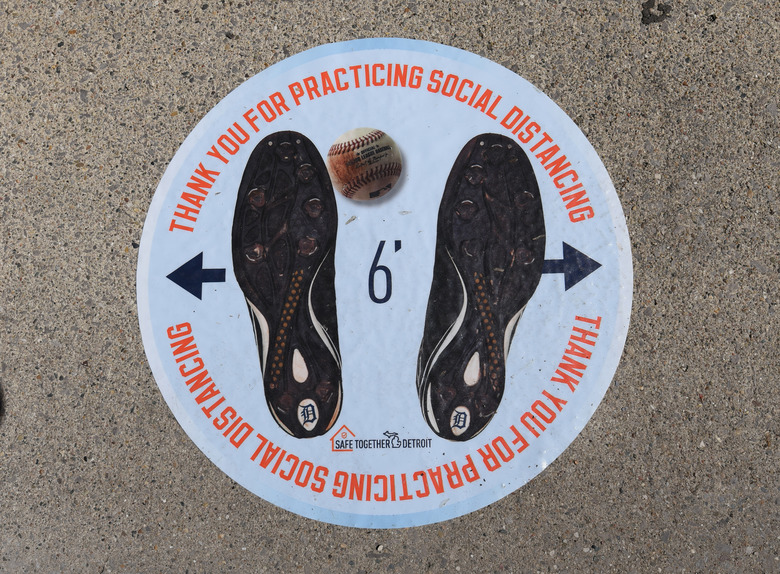

KB: I'm not aware of Long COVID as a specific difference from any other chronic illness. I will say that I've been acutely aware of how impactful COVID-19-related restrictions and isolation have been for people with disabilities. For instance, some of my local stores have added an extra table at the checkout counter, and you have to be able to reach all the way across that table in order to engage with the cashier. Well, that doesn't work if you are a person with a short reach. The isolation information is typically just a sticker on the floor — like, "Stand here to be in line six feet away." Well, if someone doesn't have adequate vision, that information is not available. So many people with disabilities who I know really felt that the world was even more unsafe for them than the average person.

I would hope that we've learned some other positive things, too. For example, working remotely is something that can happen, and you can still be productive and effective. It's been quite a culture shift over the last two years.

Hunker: As an expert in this space, what is the next frontier for accessible architecture?

KB: I don't think it's going to be shockingly different than what's happening now. I think it would be incorporating some of these new ideas and technologies that we see now in corporate campuses, university campuses, cities, and transit centers, and finding ways to move that into a legislative document. I also think it's about continuing to encourage architects to see the value in doing this, and the value in engaging people with lived experiences in their design work, so that it doesn't have to be specialized consultants. Wouldn't it be awesome if every architecture firm could say they have a person with a disability in their firm? That kind of diversity within the profession would change the way our buildings look.

Hunker: Are there many architects with disabilities in the industry?

KB: There are certainly not very many architects with disabilities. I try to connect with as many as I can meet, for sure, and I think not all architects who might qualify as having a disability identify as being disabled architects. But I think that there's increased awareness of the valuable perspective that people with disabilities bring. If you add being a person with a disability to being a designer, and bring those two things together, that is a really invaluable person to have at the table when you're doing design work. I encourage young people with disabilities to consider architecture or any design profession, if that's something that you're inclined to, because I really feel like we need more of us.

Hunker: Do you have any advice for young or emerging architects with disabilities who want to enter the profession?

KB: Connect as much as possible with firms that are doing that work. I think most of them are hungry for young designers to join them — young people who can translate between the architecture world and the disability world. There are, I don't know, about a dozen or two dozen firms across the country that do consulting like I do. And let me know — I'd be happy to help you find one!

You can keep up with Karen Braitmayer's work by following her on Instagram here.