Jeffrey Mansfield On His 'Architecture Of Deafness' Exhibit And Designing For Social Inclusion

October of each year marks National Disability Employment Awareness Month — but disability shapes our lives year-round, including in the physical spaces we encounter every day. This is something Deaf architect Jeffrey Mansfield knows and incorporates into his design and research work. It's something I also know from my experiences as a Deaf writer. In honor of this month, Mansfield and I sat down to video-chat about architecture and inclusivity in American Sign Language, though I present our conversations here in written English.

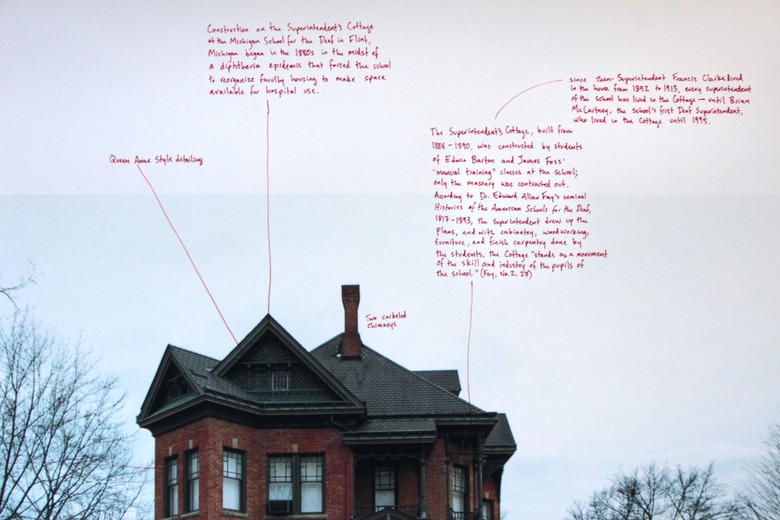

The photographs on the wall are bordered in white and inscribed with tidy red scribbles. They feature a range of buildings from different eras: columned facades with soaring cupolas, tall Victorian cottages with intricate wooden detailing, industrial workmanlike buildings for teaching carpentry and other trades, squat brick buildings in scrubby fields. These pieces of architecture, documented by the Deaf architect Jeffrey Mansfield, are joined by a common thread. They are all buildings erected at Deaf schools across the United States during the last 200 years — buildings that, in Mansfield's words, reflect evolving social attitudes towards deafness, disability, and access.

Notes on the Margins is one of the annotated installations that appeared in Architecture of Deafness, a spring solo exhibition of Mansfield's work at the Essex Art Center in Lawrence, Massachusetts. During its 2022 run from April 21 through June 4, the exhibition welcomed many regional visitors, from local community members to students from Boston-area Deaf schools. The project was the culmination of a year-long, artist-in-residence program sponsored by the Lawrence Arts Collective, an organization that promotes community-centered arts events. But it was also the latest development in Mansfield's ongoing explorations of architecture and inclusivity.

"Deaf schools were at the margins of society, physically, and mentally," Mansfield says of the inspiration behind his photographs from the Lawrence exhibition. "They were often built at the edge of a town surrounded by wilderness. I became interested in looking at that 'margin' through the physical property of the margin on the image itself, the frame."

"Deaf schools were at the margins of society, physically and mentally. They were often built at the edge of a town surrounded by wilderness."

Mansfield is a principal at MASS Design Group, a Boston-based nonprofit organization whose mission is to research, build, and advocate for architecture that promotes justice and human dignity. He began touring Deaf schools for his Architecture of Deafness project in 2017. Over the next two and a half years, supported by a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, he visited over 60 Deaf schools across North America and Europe. He entered buildings, took photographs, talked with staff and alumni, reviewed old school records, and poured through archives — also including those at the Library of Congress, another supporter of his work under the John W. Kluge Fellowship.

Even before embarking upon his research, Mansfield was well-versed in the complex contours of Deaf culture and history. Born Deaf to a hearing family, he attended The Learning Center for Deaf Children in Framingham, Massachusetts. He also visited other Deaf schools as a child, when his intuitions about the relationship between architecture and power started to emerge. "I noticed many similarities in the designs of the schools and people's experiences, so I started to wonder if there was something larger at play," he says. Mansfield went on to complete an A.B. in Architecture at Princeton University and a Master of Architecture at Harvard's Graduate School of Design.

Despite his personal and professional experience, some of Mansfield's research findings still surprised him. One school he visited, the Georgia School for the Deaf in Cave Spring, had been marked by segregation like many other Deaf schools in America — and this history turned out to be inseparable from the school's physical surroundings. The segregated Deaf school, Mansfield found, was located on a former plantation. This wasn't the only complex piece of history he witnessed. As he relates, "It was not until I actually visited [the school] that I realized it was also at the beginning of the Trail of Tears."

This Deaf school was not unique. Other state-funded Deaf schools from the mid-nineteenth century were also built along the path of forced Cherokee removal as a way of conveying public confidence in newly settled territory. They are still a bracing reminder of the social and racial power structures of early America. Most Deaf schools remained segregated for decades. Many of those former segregated Deaf schools have been closed or converted to other uses, including modern-day prisons, as in Taft, Oklahoma. As Mansfield explains, the design of Deaf schools in America tends to reflect the design of other asylums, hospitals, state institutions, and clinical treatment facilities built during their eras.

"Deaf schools don't exist in a vacuum," Mansfield says. "Deaf schools are very much integrated into the ecosystem of everything else that was happening at that time." He explains that nine salient themes emerged from his research and travels: from race and injustice to cultural histories of labor, productivity, medical pathology, and standardization, among others. In his Architecture of Deafness exhibition, he invited visitors to dig deeper into these ideas — not just as a window into the Deaf experience, but also as a provocative glimpse into larger American history and ideals.

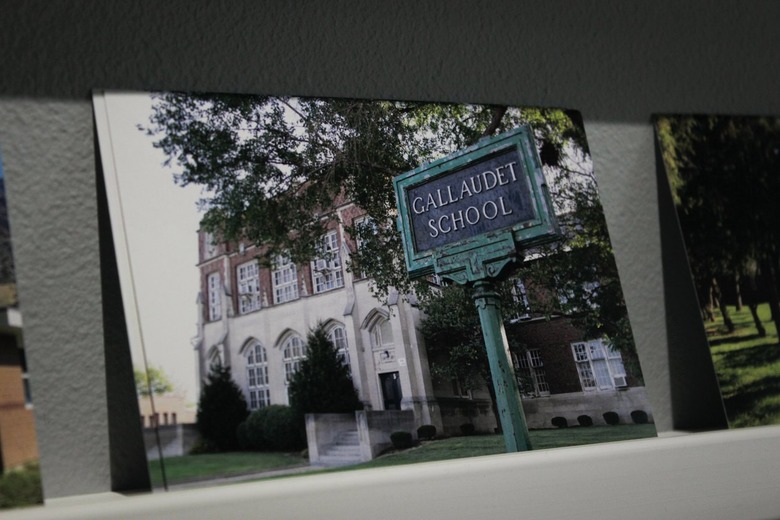

Mansfield's exhibition work also showcases the community-centered sensibility he brings to his career as an architect. In the Essex Art Center, he created an installation around a written and signed poem by the British Deaf poet Raymond Antrobus. He set out a display of postcards that prompted visitors to write down what inclusive spaces mean to them.

Centered in one part of the exhibition gallery were a circle of schoolroom chairs, all taken from different Deaf schools in the region. Some were heavy and wooden, while others flaunted retro designs from the 1950s and 1960s. These classroom chairs carried the weight of history. They invited visitors to touch and feel, to gather and reflect, and to share their stories.

"I've been looking for more sources of community narrative, because local community is where interactions between Deaf people and non-signers happen," Mansfield explains. The local Deaf community in Lawrence and in many other places, he says, does not always fit into sweeping (and often grand, white, male, patriarchal) narratives of Deaf or American history. Stories like theirs are sometimes overlooked. In his exhibition, Mansfield states, "I wanted to create a space to explore those stories."

So, one evening at the Essex Art Center, several Deaf community members from the area sat in those old Deaf school chairs and swapped cross-generational stories about education, place, and belonging. At the end of the night, one participant reflected, "We need this more than we realize."

Creating impactful architecture, in Mansfield's view, is inseparable from engaging with local communities and their stories and experiences. Thoughtful and humane design, he says, is a deeply collaborative pursuit that can elevate issues of social justice. To create inclusive spaces, architects must consider how different forms of power and human resistance have shaped the places we encounter today.

Mansfield's work at MASS Design Group, where he started working in 2015, is deeply informed by community conversations — not unlike the evening of shared Deaf stories he hosted at the Essex Art Center.

"Design processes must be co-created with the community," Mansfield says. "They must be in alignment with the community." Frequently, he explains, architects will get a design brief for a new project that has been established by a client. Instead of proceeding immediately into the project with its existing specifications, he prefers to pause and ensure that the design plan aligns with what the surrounding community needs and wants.

Mansfield and his collaborators frequently hold community forums as a part of their design process. They solicit local stories and feedback, seeking to understand the perspectives of the people who will use a particular building or space. "The process of co-creating with a community is a process of re-distributing power," Mansfield says. "It's a process of creating access to design, and it also ensures that design is something that resonates with the community."

"The process of co-creating with a community is a process of re-distributing power."

Community-centered design, for Mansfield, is always intersectional. It is intertwined with principles of universal design, as well as with ideas of radical accessibility and liberatory access coined by disability activists like Mia Mingus.

"We've thought about what the pre-conditions of access must be," Mansfield explains, referring to collaborative work with Joshua Halstead of the Critical Design Lab. "You must have safety and comfort, mobility and wayfinding, and infrastructure." Once these features are in place, a design team can consider how the space enables flexibility, ease of choice, and individual agency.

One recent community-centered project Mansfield has worked on is the J.J. Carroll Housing Redevelopment, a senior citizens' home in Boston that addresses the isolation that older people frequently experience in such settings. "We've been focusing on how we can create a sense of connection to reduce feelings of isolation," Mansfield says. Instead of long wings of individual rooms, the design breaks up the building into several shorter wings. Each floor includes a central common area and other smaller clusters, so people can choose to socialize in smaller or in larger groups. "We want to incorporate opportunities for users to self-determine how they want to engage with the space or with others," he explains.

Mansfield credits other design principles as influences on his work. Among these are the principles for DeafSpace architecture, first developed by Hansel Bauman and members of the Deaf Studies Department at Gallaudet University. DeafSpace principles address how Deaf people tend to encounter the built environment, through open and well-lit physical spaces that enable signed conversations and more strongly visual sensibilities.

One of Mansfield's first projects with MASS Design Group was a proposal for an international competition to redesign a section of Gallaudet's campus in 2016, which the firm submitted with Minneapolis studio TEN x TEN. "That was a unique project that allowed us to think expansively about how we engage with different stakeholders, people who represent the community, people who represent different physical and sensory needs," he says.

While considering the perspectives of different Deaf and DeafBlind students and faculty members, and also in collaboration with the Japanese-British Deaf performance artist Chisato Minamimura, the team developed a multisensory master plan for the Gallaudet campus. In addition to visually-oriented DeafSpace principles, the plan incorporated strongly tactile elements through warm materials and finishes, native plants, custom designed railings, curbing and floor surfaces suited to the navigation patterns of blind and low-vision users, and Braille signage. It enriched the olfactory environment through a pine grove, water and mist, and flowering plants arranged alongside seating areas. And it incorporated sound as a physical — and not solely as an acoustic — phenomenon through specifying wood finishes to transmit vibrations and extend users' sensory reach.

"We didn't win [the competition] with that project," Mansfield says, "but it led to an interesting shift in our practice where we started looking at the impact of multisensory architecture."

Two recent projects have furthered Mansfield's interests in multisensory design. The first, a set of design recommendations for the James Castle House in Boise, Idaho, aims to instill a Deaf perspective into the experiences and work of the self-taught Deaf artist James Castle. The local Boise architect Byron Folwell first restored the house in 2017-18. "We've been envisioning a plan of how the James Castle house could tell the story of James Castle in a way that doesn't diminish the impact his deafness had on his art," Mansfield says. After workshops with curators, historians, scholars, museum professionals, and Deaf community leaders, the team identified multisensory design as a strategy that could place visitors in closer proximity to what the artist himself might have experienced.

The design recommendations identify several spaces that could place visitors "in James Castle's shoes." One of those spaces, a shed next to Castle's family home, offers the opportunity to immerse visitors in the rich smells, lighting, visual surfaces, and rough or smooth textures that informed the artist's creative process. The aspiration for these recommendations — which include the configuration of spaces, the availability of ASL interpretive content, and a permanent enclosure for the shed — is to help James Castle House visitors feel more engaged with James Castle's story. For Deaf and hearing visitors alike, Mansfield says, the space and its interpretive environment could lead to a deeper "sense of connection" with the artist and his unique way of encountering the world.

A second project, a collaboration with Mahlum Architects and with Christopher Downey of Architecture for the Blind, imagines a living skills center for the Washington State School for the Blind in Vancouver, Washington. The team paid close attention to the acoustics of the space and included different tactile materials that can convey information about its use and purpose. Various floor treatments guide users' navigation and speed of movement, for instance, while natural materials welcome people to touch and engage with walls and other surfaces. Olfactory cues in the design of the landscape, including a rain garden, offer a sense of orientation as well as delight. All these details, Mansfield explains, aim to create a warmer sense of home for the students who live and learn there.

"Many of our projects come back to a sense of joy," Mansfield explains. When architects collaborate with a community, they can co-create spaces that allow people to gather and feel safe. "Joy is a type of belonging, and we think about how we can foster that through spaces that respond to the community's needs."

"Joy is a type of belonging, and we think about how we can foster that through spaces that respond to the community's needs."

And what about his Architecture of Deafness project? What is next? Though this spring's solo exhibition is done, Mansfield plans to keep adding to the project through filming different local Deaf community members and their stories. He also hopes to take the exhibition on the road through an Airstream travel trailer, collaborating with more Deaf artists and curators to bring rich stories of Deaf histories and spaces to different audiences.

"This could give the community the opportunity to share their experiences in many different locations," Mansfield says. "I hope to build a living archive of those experiences and create a space that allows for exhibitions and experiences that can spark conversations between the Deaf community and their local community."