Times You Can (& Can't) Outsmart Tradition When Building Your Own Home

Homes are built certain ways for certain reasons. My wife and I built our house in a remote, rural area, telling ourselves the privacy was going to be great. Almost immediately after we moved in, two more houses went up across the street. The left-hand house was constructed by builders hired by a young couple. The right-hand house, meanwhile, is an exceedingly ordinary affair that was built by a young tradesman himself, with the occasional help of friends. And my house? It was designed by me and my wife, built mostly by me ... but with a far less traditional approach to almost everything.

If a big, bad wolf were to strut down our street, intent on blowing some houses down, then the tradesman's house would be the proverbial "brick house" — it wouldn't budge at his huffing nor puffing. Built like a tank, it's modestly sized and extravagantly rectangular, with tiny windows of the sort you'd see someone selling ice cream through at the beach. The couple's house is the "stick house" in this story: It's lovely but ordinary in every way, and I fear it might not last through the wolf's windy attack. Then there's my house. It's certainly not likely to be blown down, but an enterprising wolf could find, in my innovations, ways to make me very uncomfortable, all because of the ways I've both outsmarted — and been outsmarted — by tradition.

That's why my home makes a great case study in what happens, both good and bad, when you mess around with the sacred traditions of ordinary home construction.

You CAN outsmart traditional insulation

In homebuilding, the most promising areas for thumbing your nose at tradition are probably the things you don't think much about in daily life. For example? Insulation. If we had gone through with our original insulation plans, a visiting big bad wolf would have run up against metal-clad, wood-framed, concrete-filled walls. That's because in our casting about for the cheapest but most effective version of everything, we encountered a concrete foam product called aircrete. Used both as insulation and as a building material, aircrete (also sold as air krete) is lightweight, inexpensive, fireproof, vermin-proof, nontoxic, mold-resistant, and a pretty good acoustic barrier. Oh, and it has an R-factor from 3.9 to as high as 6 per inch, which is better than fiberglass and potentially on par with closed-cell spray foam.

We ultimately decided against it, because of some peculiarities of our barndominium's wall system — and concerns about over-insulating electrical wiring — but we do plan to use it in the future as a material for our DIY shed. In general, though, aircrete is a a kooky idea whose time has come.

That's just one example, though, of my overarching point that with insulation, you can break the rules. Innovations up the ante compared to the good ol' standard insulations (fiberglass batt, rockwool, spray foam, polystyrene, etc.), and you absolutely should look at quirky options like cellulose batt insulation to recycled denim to wood fiber. There's no need to be hemmed in by tradition. If you go this route, just be aware you could get challenged by a local inspector who isn't familiar with it and thinks you've lost your mind: Preparation and good communication among everyone involved is the solution to any inspection hiccups you might encounter.

You CAN'T outsmart your actual building materials (and their proper use)

Insulation is one thing, but building materials is another. Let's go back to aircrete, for a second. Aircrete is a wonderful insulator and has a lot of great characteristics, but you probably don't want to use it at large scale as a building material, because some research indicates there are potential problems with that approach.

This is perfectly emblematic of other building materials you may be eyeing but which you should really reconsider — such as cob houses, rammed earth, adobe, to say nothing of wattle and daub. These materials are too traditional to be considered traditional these days. Hint: if your house requires something called an "earth mason," you might be in for some workflow and supply chain issues. Similar but more, umm .... innovative approaches include hay bales and concrete made with sawdust (called, rather unfortunately, "dustcrete").

The point here isn't to poo-poo anything that's not represented by a trade group. My wife and I considered all manner of heterodox building notions. Each method has its disadvantages (like poor insulation value or extensive labor requirements) that have been evolved out of the building materials you'll find at Lowe's. There's plenty of room for being an oddball, but when it comes to building materials, stick with the modern ones unless you enjoy headaches.

You CAN put your personality into the floorplan

Functional stuff like walls and insulation are important. But as any emo teenager will tell you (if you can get one to talk), setting yourself against tradition begins with how things look. Designing a home is a rewarding and frustrating experience, and you're almost certain to design something unorthodox, since you probably don't know how to design something orthodox. That can be a feature rather than a bug, and this is an area where you don't want to shortchange yourself.

For example, our barndominium ended up being so tall (the incremental costs from 12- to 15-foot sidewalls were negligible) that we ended up with a kitchen and living room with vast, open ceilings ... to say nothing of the vast, open heating and cooling bills that we now "enjoy." But it felt right, and still feels right. Ditto for the massive loft with two bedrooms and an open craft room. We let our personality trump the traditional, and this is an area where you should do that.

Your vibe, of course, will be different. Maybe you'll make the transitions from indoors to outdoors seamless in the manner of a traditional Japanese dwelling, or you'll eschew the open floorplan for a series of functional stalls for every little avocation you're inspired to. Don't fear it. It's just a floorplan. Let yourself be creative, because that's the fun of this. But stop yourself at a certain point, because...

You CAN'T skip the research (or pragmatic considerations) if you're going to do a whimsical floorplan

If you're going to have fun with your floorplan, great — but whenever you decide to break a rule, first look into why that rule exists. A lot more can go wrong than you think, from bathroom location, to acoustics, to orientation to the sun, to sufficient storage. Look for lists of these matters and study them well, because the resulting problems will haunt you forever.

My particular trouble was with a staircase. Our earliest floorplans had an upper floor designed as short sleeping lofts, accessible by retractable ladders. When the sidewalls grew to 15 feet, we realized that we could frame out proper rooms up there. That introduced all manner of complexities we hadn't planned for, from new code compliance demands to windows we hadn't planned for. It also meant proper furniture. All of this — especially the prospect of carrying furniture up ladders — made it obvious that we'd need a staircase. We reclaimed space for the stairs by appropriating about a third of our very large living room.

That left us with a merely large living room, but one with practically no wall space. One wall became an open staircase, one was open to the kitchen, one had 12 feet of glass patio doors, and the other was almost entirely windows. This made for something of a design nightmare. I am, to this very day, in the process of replacing the wall of windows with a couple of smaller ones. This all could all have been avoided by simply designing a staircase in the first place, like normal people, instead of trying to be unconventional for the sake of it.

You CAN take innovative approaches to everyday things like plumbing

Whether because of arrogance, stupidity, or some delusional sense of self-reliance, I occasionally find myself thinking I can do things better than people who, you know, actually understand how to do things. Sometimes I win, sometimes I lose. Occasionally I find that many of the professionals are with me, as tradition is giving way to genuinely better options. Here is an example from my least favorite part of homebuilding: Plumbing.

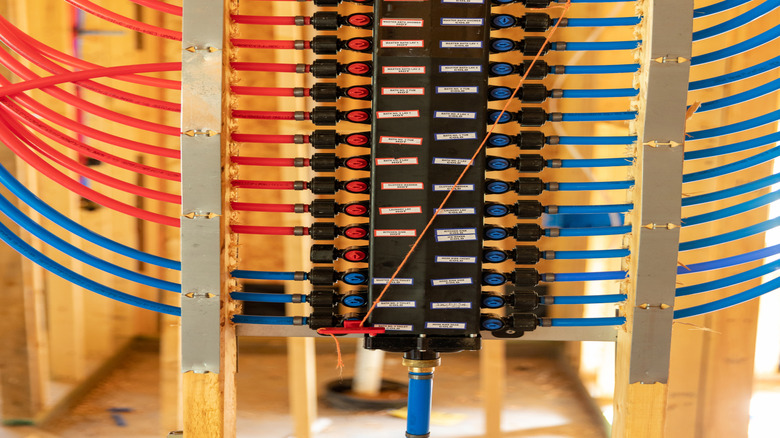

I don't remember how I even became aware of it, but early in the process I decided that a PEX manifold system was the way to run water to my fixtures. If you haven't seen these glorious things, they're basically distribution points for water from which hot and cold water are routed in separate pipes to each individual fixture (or, at least, to no more than a couple of fixtures). Imagine a circuit breaker panel where every breaker is tied to a single receptacle; it's like that. This makes for far fewer joints in the PEX (I basically have none except at the manifold and the fixtures) and, therefore, drastically fewer opportunities for leaks. I can also turn off water to individual faucets, which is great when you're remodeling the kitchen for the third time.

Another, somewhat less accepted, approach I tool also worked out well: a gray water disposal system. But let's save that for the discussion of my most unsuccessful bid to buck tradition, and one place where you should absolutely learn from my mistakes.

You CAN'T break any rules about septic tanks, that's for sure

So, I intentionally skirted around septic system sizing requirements. Hear me well on this one: Don't mess around with septic issues.

Where I live, you have two options: Use a traditional septic system, or poop somewhere else. My property didn't perc well, but there was a corner that would support a septic system sized for a one-bath home. So, we designed a one-bathroom home. One does not simply have one bathroom for a family of six, and one does not game the local septic regulations. Septic systems are sized based on the number of bathrooms because it represents a home's potential usage (and thus, production of wastewater). When the water table rose that first winter, our undersized septic system made itself known in a manner that can't be discussed in polite company. It happened in the dirt road we live on, fortunately, thanks to a sewer backflow preventer.

Fortunately, a gray water system -– used to irrigate various parts of the property -– basically eliminated the problem, but I still have to keep an eye on things. Rain causes septic system problems for us, as the leach field is sandwiched between rain and groundwater. This is something I'd much rather not have to think about it, but I'll probably have to keep an eye on it for the rest of my life. It all works out, even the worst mistakes... but sometimes at a pretty high cost.